The U.S. needs to increase the number of immigrants entering our country each year substantially to grow its competitive advantage and expand our future workforce, according to immigration scenarios prepared by researchers at George Mason University in a study commissioned by FWD.us1. Without boosting legal immigration significantly now, the U.S. will sacrifice its position as the world’s largest economy by 20302 and leave the reserves of vital programs—like Social Security—depleted by 2034.3

Increasing Future Immigration Grows the U.S.' Competitive Advantage

U.S. Future Immigration Highly Impacts U.S.' Future Global Economic Standing

$47 Trillion

$50 Trillion

$28 Trillion

- Very High Immigration

(2.4 million immigrants annually) - High Immigration

(1.8 million immigrants annually) - Recent Immigration

(1.2 million immigrants annually) - Low Immigration

(0.6 million immigrants annually) - Zero Immigration

(no immigration)

- Very High

- High

- Recent

- Low

- Zero

Note: U.S. projections are constant 2018 dollars. India and China projections are based on constant 2016 dollars. GDP in MER is gross domestic product as value of goods and services at market exchange rates. GDP in PPP is gross domestic product at purchasing power parity adjusting for standards of living across countries.

“By doubling immigration levels today, Congress can ensure the U.S. remains a global economic leader for decades to come.”

The United States’ economic future is deeply tied to the makeup of its population. The size, age, and skills of the population—all greatly impacted by immigration—will help determine the U.S.’ ability to stay competitive with other countries, support critical programs like Social Security, and grow an economy that creates jobs.

Without increased immigration, the coming decades will see an increasingly older U.S. population, with the ratio of seniors to working-age adults increasing. This means that aging Americans will draw on safety net programs like Social Security more quickly than working-age people will be able to support them. It also means more of America’s resources will be devoted to supporting the aging population than to growing the economy through new investments and innovation.

If the U.S.’ working-age-to-senior ratio is not maintained, economic growth will slow compared with other nations, draining our social safety nets and sacrificing our current position as the world’s economic leader. In fact, if current U.S. population trends continue, the U.S. economy will fall behind China’s by 2030, and be only three-quarters of China’s economy by 2050.

However, this decline is not set in stone. The United States can reverse these trends and increase economic growth. To do so, elected officials in Congress should strategically increase immigration, and reject calls from immigration restrictionists to cut legal immigration levels. As projections show, by increasing immigration—and by creating a humane, orderly system for employment- and family-based immigration—the United States can maintain its global leadership and invest in a strong economic future for all Americans.

Projections show that U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) could double and grow as large as $47 trillion in today’s dollars in 2050 if immigration levels were doubled to more than 2 million new permanent and temporary immigrants each year. Per capita, this would lead to a 3% increase in average income by 2050 for all Americans compared with keeping immigration at recent levels, and a 7% increase compared with a zero immigration scenario. Compared with recent immigration levels of around 1.2 million immigrants per year, doubling of immigration now would greatly expand the economic future of the country.

Congress needs to act with urgency to improve and expand immigration pathways to maintain our global leadership in the decades to come. Delaying major immigration reform hurts our economy and millions of families. The U.S.’ economic and demographic future is directly linked to future immigration to our country. The status quo on immigration is unacceptable for our future prosperity. Congress and the Biden Administration have an opportunity to put America on firm economic footing that looks to our future by increasing immigration levels today in a humane, orderly way.

Our population projections rely on the cohort component method used by the U.S. Census Bureau and other demographic research organizations. Projections are long-term forecasts, or estimates, based on what we know about populations today and projecting those trends into the future. They allow for different assumptions—like varying immigration rates—to lead to different projected outcomes.

In this study, baseline population data were drawn from the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) by age, sex, race, and place of birth (immigrant/nonimmigrant). Necessary demographic components for population projections were drawn from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 national projections, including mortality, fertility, and migration rates.

People both enter the U.S. (immigrants) and leave the U.S. (emigrants).4 The combined effect leads to a net migration rate, with a positive rate indicating more immigrants entering than emigrants leaving. Different levels of immigration were added to the net migration calculation while keeping emigration constant across all scenarios.

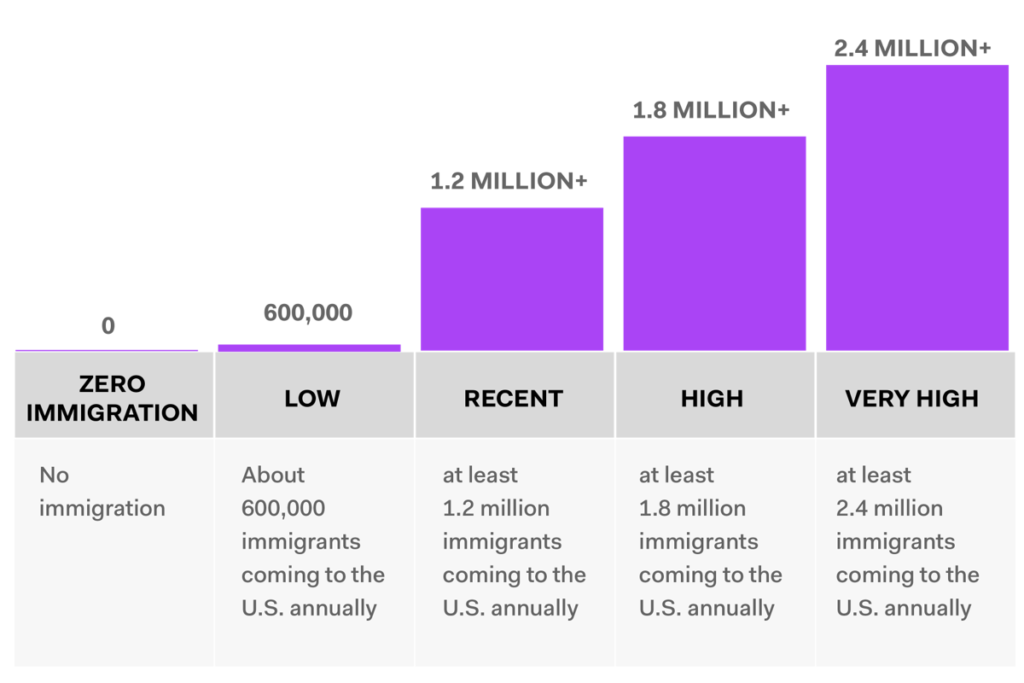

The study considers five immigration scenarios, based on immigration levels in 2017:

- Zero immigration

- Low—about 600,000 immigrants coming to the U.S. annually

- Recent—at least 1.2 million immigrants coming to the U.S. annually

- High—at least 1.8 million immigrants coming to the U.S. annually

- Very high—at least 2.4 million immigrants coming to the U.S. annually

The resulting population growth was estimated for each immigration scenario, keeping other population dynamics constant.5

Economic growth is based on population projections for demographic groups using economic and employment data from the 2018 ACS. These economic projections do not take into account sudden economic shocks, slumps, or recoveries. Economic growth is expressed as GDP using constant 2018 U.S. dollars, calculated as the total income of the U.S. population. Efforts were made to make these U.S. GDP measures comparable to international GDP measures that use constant 2016 U.S. dollars.

Models using different compositions for future immigration (for example, more highly skilled individuals) were adjusted based on immigrant education levels. Population projections calculated the relative size of the senior population (aged 65 and older) compared with the working-age population (16 to 64). Similarly, estimated payroll taxes were based on recent income data from the Current Population Survey, combined with trust fund totals from the Social Security Administration. These data were used to calculate inflow and outflow contributions from the Social Security Trust Fund. Payroll taxes were assumed to remain constant throughout the projection period.

Finally, recent events associated with the COVID-19 pandemic likely led to lower immigration to the U.S. in 2020. The pandemic has also led to lower GDP in 2020. The models do not reflect this slump in population and economic growth. It is assumed that this drop in 2020 and immediate years thereafter will rebound. Separate models were calculated taking into consideration this decrease in immigration and GDP, and showed minimal differences for long-term projections.

Population Growth

Future U.S. immigration will drive future U.S. population growth

With a larger share of America’s workforce aging, immigration is essential in growing the U.S. workforce and preserving our global competitive edge.

Future Immigration Highly Impacts Future U.S. Population Growth

496 Million

404 Million

- Very High Immigration

(2.4 million immigrants annually) - High Immigration

(1.8 million immigrants annually) - Recent Immigration

(1.2 million immigrants annually) - Low Immigration

(0.6 million immigrants annually) - Zero Immigration

(no immigration)

- Very High

- High

- Recent

- Low

- Zero

The study’s projections show the U.S. population would grow to nearly 500 million people by 2050 if U.S. immigration levels were doubled, about 100 million more than if immigration levels were kept at recent levels.6

By contrast, it is expected that the U.S. population in 2050 would be only 40 million larger than it is today if immigration were lowered by about half, as proposed by immigration restrictionists in Congress. And, if immigration were stopped altogether, the size of the U.S. population would be about the same as today, at roughly 330 million.

Without doubling immigration, the U.S. would be about the same population size as Nigeria in 2050, making the U.S. the world’s fourth-largest population at around 400 million people. If immigration dropped by half, or stopped altogether, the U.S. population would rank even lower globally, in fifth or sixth place, or around the population size of Indonesia or Pakistan in 2050.

Doubling the number of immigrants would put the U.S. on par with other immigrant-receiving countries competing for top talent. In this “very high” immigration scenario, the annual number of immigrants would represent about 0.7% of the total U.S. population in 2020, similar to but still less than peer countries like Canada (0.9%) and Australia (0.8%).

More critically, increasing immigration would also increase the working-age population, combating the effects of an aging population and ensuring it is sufficiently supported.

Future Immigration Highly Impacts Senior To Working Age Ratio

31

37

- Very High Immigration

(2.4 million immigrants annually) - High Immigration

(1.8 million immigrants annually) - Recent Immigration

(1.2 million immigrants annually) - Low Immigration

(0.6 million immigrants annually) - Zero Immigration

(no immigration)

- Very High

- High

- Recent

- Low

- Zero

Projections indicate, for example, that 37 seniors (65 and older) would live in the U.S. in 2050 for every 100 working-age people (ages 16 to 64) if immigration is kept at recent levels. This ratio is much higher than today, when an estimated 27 seniors live in the U.S. for every 100 working-age people.

If immigration levels doubled, however, the senior-to-working-age ratio in 2050 would be 31 for every 100, lower and more similar to today’s ratio. Consequently, doubling immigration would keep the status quo for the senior-to-working-age population balance.

Slowing the rise of the senior-to-working-age ratio is critical for Social Security’s solvency. At recent immigration levels, it is estimated that the Social Security Trust Fund in 2050 would pay out $337 billion more dollars than income received into the trust fund. If immigration levels were doubled in the decades ahead, however, the net disbursement would be much lower in 2050, around $139 billion.

Undoubtedly, increasing the number of immigrants entering the U.S. each year will lead to a higher share of immigrants in the U.S. population. Projections indicate that doubling immigration flows would grow the immigrant share from 14% today to 29% of the total U.S. population by 2050, comparable to recent immigrant shares in Canada (22%) and Australia (30%). In comparison, if immigration levels remained at recent levels, immigrants would make up 19% of the U.S. population in 2050.

Without a substantial increase in immigration, the U.S. population will grow only marginally in the decades ahead. Keeping the status quo on immigration policy will prohibit the U.S. from age-balancing its population and will prevent us from maintaining our economic standing in the world.

Economic Growth

Future U.S. immigration will significantly shape U.S. economic growth

U.S.’ economic growth is highly dependent on future levels of immigration to the U.S. In raising immigration levels, the U.S. economy can grow substantially in the decades ahead as more working-age people contribute to the economy.

Future Immigration Highly Impacts U.S.' Future Global Economic Standing

$47 Trillion

$37 Trillion

- Very High Immigration

(2.4 million immigrants annually) - High Immigration

(1.8 million immigrants annually) - Recent Immigration

(1.2 million immigrants annually) - Low Immigration

(0.6 million immigrants annually) - Zero Immigration

(no immigration)

- Very High

- High

- Recent

- Low

- Zero

Note: Projections are constant 2018 dollars. GDP in MER is gross domestic product as value of goods and services at market exchange rates.

“Increasing immigration substantially will increase overall U.S. GDP in the decades ahead.”

The study’s projections show that doubling immigration could expand the economy in 2050 to more than twice its current size. U.S. GDP could be as large as $47 trillion within three decades, compared with $37 trillion if recent immigration levels continue, and $29 trillion if immigration into the U.S. were stopped altogether. In other words, if the U.S. does not double our immigration levels, we risk losing out on 25% of additional economic growth by 2050.

A substantially larger U.S. economy through increased immigration offers many benefits.7 Government fiscal balance sheets will be in a healthier position with a larger working-age population, including longer solvency of important federal and state benefits. A larger U.S. economy also keeps the U.S. geopolitically strong, especially given the acceleration of economic growth in China and India. And average income for Americans, or GDP per capita, is projected to improve, about 3% higher in 2050, with doubled immigration compared with recent immigration levels.

The majority of recent U.S. immigrants enter on family-sponsored visas, which do not impose education or skill requirements.8 Immigration restrictionists have proposed massively cutting family-based immigration. But if the composition of immigrants were inverted—where the majority of immigrants entered through labor pathways, or particularly geared toward more highly educated immigrants—the economy in 2050 would be smaller ($38 billion in the “very high” immigration scenario) compared with an immigration system where majority-family immigration is maintained.9

Majority-Family Immigration Lifts Future GDP More Than Majority High-Skilled, But Both Systems Equally Increase Future GDP Per Capita

$47 Trillion

$38 Trillion

$94 Thousand

$93 Thousand

- Very High Immigration

(2.4 million immigrants annually) - High Immigration

(1.8 million immigrants annually) - Recent Immigration

(1.2 million immigrants annually) - Low Immigration

(0.6 million immigrants annually) - Zero Immigration

(no immigration)

- Very High

- High

- Recent

- Low

- Zero

Note: Projections are constant 2018 dollars. Majority family immigration maintains the current immigration composition, which is about two-thirds family-based immigration. Majority high-skilled immigration inverts immigration composition to two-thirds highly educated immigrants.

At the same time, a more highly skilled immigrant system would increase U.S. GDP per capita moving forward. When doubling immigration, Americans would see a 3% increase in average income in 2050 compared with keeping immigration at recent levels. That increase expands to 7% when comparing a doubled-to-zero immigration scenario.

Regardless of the family-sponsored versus high-skilled mix, levels of immigration need to be increased overall for stronger future economic growth. That means that both family-based and labor-based immigration must be increased immediately.

U.S. economic growth and our continued global economic leadership depend on expanding opportunity supported by a sufficiently large working-age population, which means implementing humane, orderly ways to increase immigration levels of all kinds. Expanding immigration will also create a stronger foundation for vital benefit programs like Social Security.

There is no time for delay—Congress must act now and pass commonsense legislation that can quickly expand immigration. This immigration reform must keep families central, while also attracting a much higher number of high-skilled immigrants. Bipartisan solutions exist that can be implemented now. We urge Congress to move America forward by increasing immigration today.

A report of the FWD.us Education Fund, Inc.

- Research team included Justin Gest (George Mason University), Jack A. Goldstone (George Mason University), Annie Hines (University of California Davis), Erin Hofmann (Utah State University), and Guizhen Ma (Utah State University). Their complete study can be found here. The study was reviewed by an expert panel: Bryan Caplan (George Mason University), John S. Earle (George Mason University), Dowell Myers (University of Southern California), John May (George Mason University), Alexander Nowrasteh (CATO Institute), Kevin Y. Shih (City University of New York ), Sita N Slavov (George Mason University), and Chad Sparber (Colgate University). This report was written by FWD.us staff.

- International comparisons in this report are based on market exchange rate (MER) gross domestic product. If using purchasing power parity (PPP) gross domestic product, the U.S. economy is smaller than China’s economy in the decades ahead under every immigration scenario presented in this report.

- Based on an assessment by the Social Security Administration for its middle scenario, similar to this report’s recent immigration scenario.

- Migration includes both foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals.

- The study uses constant net migration rates. Consequently, the actual number of immigrants projected to enter the U.S. changes year to year, depending on the scenario.

- According to data from the Department of Homeland Security, the number of new lawful permanent residents (LPRs) has dropped in recent years. This has led to a slowing growth of the U.S. immigrant population overall. Various policies begun by the Trump Administration, including executive orders banning the entry of certain nationalities and COVID-19 restriction measures have lowered immigration in recent years. And, given the pandemic, it is assumed that immigration decreased further in 2020. For example, completed applications for lawful permanent residency (LPR) by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services dropped by 23% in 2020 compared with fiscal 2019. The projections in this report, however, rely on immigration flows in 2017, prior to the most recent slowdown. It is expected that new executive actions in the Biden Administration as well as pending action in Congress will lead to a return to 2017 immigration levels in 2021 and 2022.

- Net fiscal impacts were not estimated in this study, but studies indicate that changing the volume of immigration to the U.S. has a minimal negative fiscal impact overall, if any. This is because the fiscal costs of educating and assisting children of immigrants is largely outweighed by the labor productivity and taxes provided by a youthful immigrant population.

- As global education levels have increased in most countries, incoming immigrants into the U.S. have increasingly had more education, regardless of whether they enter the United States via family or labor visas.

- This is due, in part, to high-skilled immigrants leaving the U.S. more frequently and also having fewer children. These factors decrease the total U.S. working-age population over time, and thus limits economic growth.

Tell the world; share this article via...

Get Involved

We need your help to move America forward. Learn what you can do.