To lower inflation,

America needs more immigration to alleviate national labor shortages

"A new FWD.us study developed in collaboration with George Mason University (GMU) aims to quantify the extent to which decreases in immigration before and during the COVID-19 pandemic have contributed to inflation for all American consumers."

Overview

In 2021, the U.S. began facing historic levels of inflation. Experts have posited many factors to explain the increase, including broken supply lines, rising fuel prices, and pent-up demand. But these contributing factors have largely abated, and yet, inflation remains.

Economists, including those at the Federal Reserve, have identified persistent worker shortages, and more specifically immigrant worker shortages, as a major contributor to rising inflation. When labor is in short supply relative to demand, employers offer higher wages, which are in turn passed on to consumers, leading to rising prices. While these worker shortages have occurred for many reasons, a significant driver is the lower number of immigrants who have entered the U.S. in the past several years.

A new study developed in collaboration with researchers at George Mason University (GMU) aims to quantify the extent to which decreases in immigration, already begun before and nearly frozen during the COVID-19 pandemic, have contributed to inflation for all American consumers. In doing so, the analysis provides a snapshot of the future American workforce which, if not increased by immigration, can spell economic pain for many years to come. By examining immigration as a contributor to inflation, the report seeks to demonstrate how the challenges of an aging workforce, accelerated by the pandemic, can play into rising inflation in the near and long terms, amidst other compounding economic factors that can also raise prices.

Congress and the Biden Administration should immediately find legislative solutions to increase legal immigration, or risk future inflationary spikes. Our current immigration system requires modernization to meet the economic demands of a new century. This pathway is far preferable to the current track of raising interest rates to slow the economy and potentially land the economy into recession.

Low immigration and rising inflation during the COVID-19 pandemic

At the onset of the pandemic, the U.S. saw a sudden population shift to new areas, including suburbs, smaller cities, and more southern locations. And as people moved, their demand for goods and services went with them. At the same time, their destinations faced significant labor shortages, especially in sectors and types of jobs that the resettled remote workers would not fill. In fact, these new destinations needed even more service and manual labor jobs, to meet the unexpected consumer demand

The presence of an immigrant workforce typically can help local communities mitigate sudden labor shortages, particularly in industries such as construction and hospitality. But, as immigration decreased before and during the pandemic, these jobs remained largely unfilled, leading to extreme labor shortages and rising wages. In other words, inflation rose in part because of a tightening labor market.

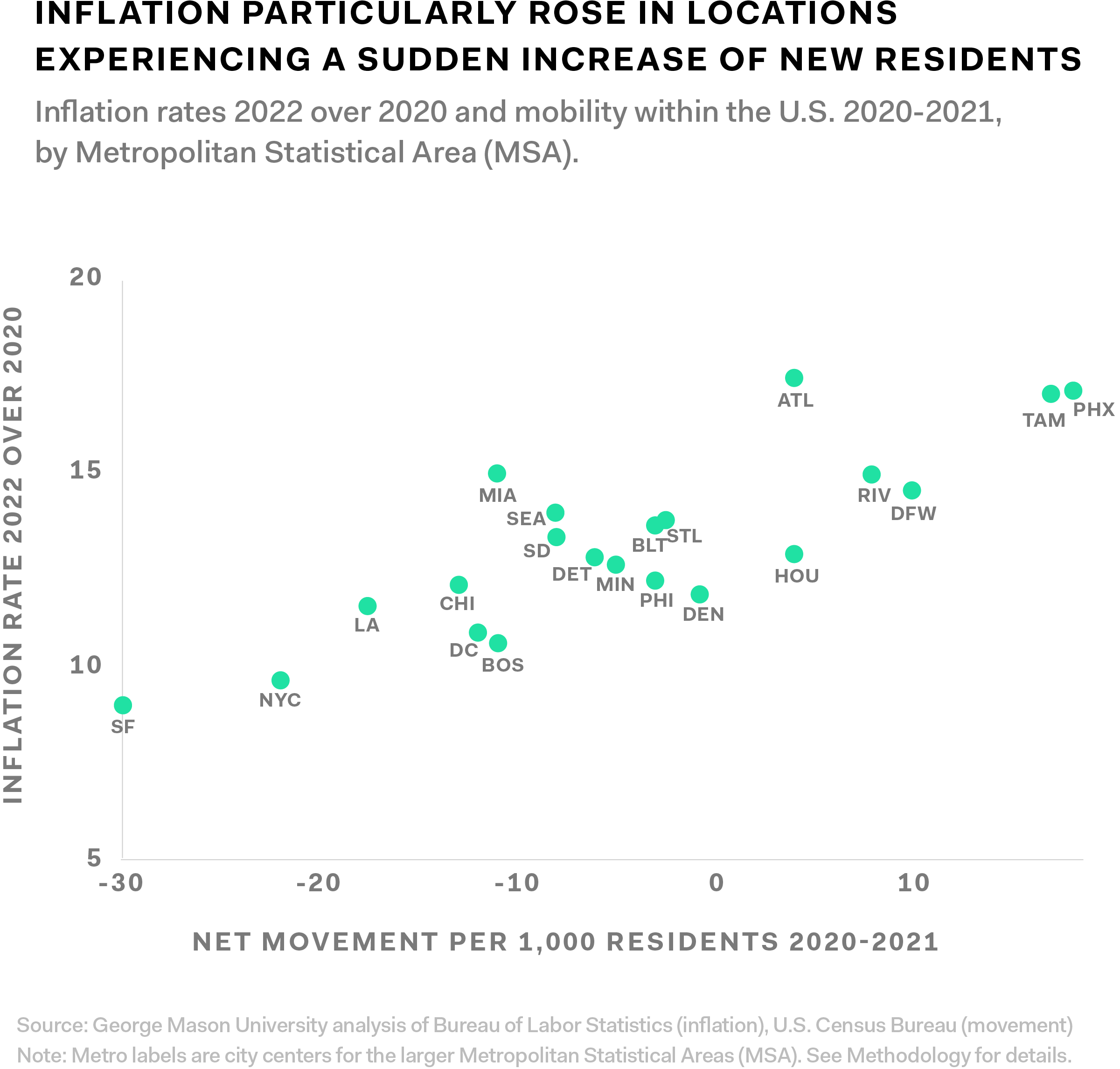

Mason researchers find that this sudden population shift is associated with a squeeze on labor supply as well as upward pressures on wages and home prices. These upward pressures can lead to higher wages that then lead to increasing costs for consumers. The data analysis estimates a 2.5 percentage point increase in inflation, or $1,500 annual increase for the average household in 2021 to 2022, for those moving from a city experiencing some of the largest population losses (like San Francisco and New York City) to a destination experiencing some of the largest population gains (like Atlanta and Phoenix).

But this inflation may not have occurred if a regular, and growing, inflow of immigrants had been added to the U.S. workforce. These worker shortages resulted partly from a freeze on legal immigration pathways during the pandemic, preceded by years of decreased legal immigration levels under the Trump Administration. During this period, economists estimate that nearly two million working-age immigrants who would have ordinarily entered the U.S. were unable to do so. After Trump Administration immigration limits, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) backlogs, the closure of Department of State (DOS) consulates overseas, border restrictions like Title 42, and overall reduced global movement during the pandemic, the U.S. now needs to restore its immigration system and rebuild its workforce.

In locations experiencing a surge of new U.S. residents, data analysis shows that some of the sharpest wage increases, which reflect worker shortages, occurred in industries typically supported by a large number of immigrants, including construction and hospitality.

"Increasing immigration would help prevent inflation and stabilize the workforce."

Fortunately, nationwide worker shortages in industries typically supported by immigrants began to subside by the end of 2022 as legal immigration pathways returned and the inflow of immigrants increased month by month. This return to pre-pandemic immigration levels has also coincided with recent reductions in inflation. But these economic challenges—inflation, a strained workforce, and labor market mismatches—will likely continue long after the pandemic is over, and failing to modernize our immigration system will leave the U.S. economy increasingly vulnerable. Increasing immigration would help prevent inflation and stabilize the workforce.

As an example, FWD.us data analysis examines how one legal immigration pathway used by the Biden Administration—humanitarian parole—has offered a timely and crucial reduction in labor shortages, and likely contributed to lower inflation in recent months. The lesson: policies designed with substantial humanitarian benefit can be good for the economy, and immigration policy that responds quickly to market shifts can stabilize prices for consumers and offer relief to employers, while also providing new workers an opportunity to contribute their skills and knowledge to the U.S. economy.

"Projections show that, without immigration, the U.S. working-age population will not grow in the years ahead."

The pandemic as preview for longer-term demographic challenges

For the past two decades, the U.S. population has been aging as the baby boomer generation reaches retirement age and fewer young people enter the workforce. This is leading to a slowing growth in the working-age population, with fewer people entering the workforce while even more leave it. Meanwhile, America’s demand for goods and services persists, with fewer people lined up to provide them.

The warning bells for this coming demographic crisis in the U.S. have been sounding for some time, but the pandemic put it in sharp relief as a demand for services shot up without an available labor supply. While the majority of workers kept and have kept going to their physical locations for their jobs, for many millions, remote work has been a massive change with huge societal consequences. In essence, these compounding forces – shifting population centers and lower immigration – led the U.S. workforce to experience the effects of long-term demographic decline in a very short period of time. By examining what happened during the pandemic, including the relationship between reduced immigration and increased inflation across the U.S., we can better anticipate what lies ahead if we do not fix our immigration system. The pandemic experience simulated the future challenges the U.S. workforce would face without increasing immigration levels.

Demographic projections produced by Mason researchers show how demographic factors like aging are reshaping the U.S. population, and more specifically the U.S. workforce. Projections show that, without immigration, the U.S. working-age population will not grow in the years ahead. In fact, the U.S. needs to increase immigration levels, not only to make up for the immigration shortfall seen over the past few years, but also to ensure a growing labor supply for the rest of this decade. Without a growing workforce fueled by increased immigration, the U.S.’ global edge will soften, leading the country to become less competitive for talent, innovation, and productivity. No other country that has seen its prime-age working population drop has continued to grow economically. The results of working-age population decline are affordability crises for all Americans, everyone is poorer on average, as well as substantial global competitiveness and security challenges.

Increasing immigration would also have other positive indirect effects, including raising wages for Americans, while at the same time reducing the risk of future inflationary episodes. Projections show that, under an increased immigration scenario, Americans would earn, on average, $1,000 more annually by 2040 compared to a scenario where immigration levels are held constant. By contrast, if the country were to return to significantly lower levels of immigration (similar to those experienced during the pandemic), the average American would stand to earn $16,000 less annually by 2040 than if immigration levels were increased.

With job openings at historically high levels and an employment rate for prime working-age individuals at its highest since 2001, immigration is one of the most immediate and effective economic solutions to lowering inflation and stabilizing it for years to come.

What happened in new destinations across America coming out of the pandemic is what would happen across America in the years ahead as labor demands increased, the population aged, and the economy grew, but the workforce did not grow with it.

"If the country were to return to lower levels of immigration seen during the pandemic, the average American would stand to earn $16,000 less annually by 2040 than if immigration levels were increased."

Congress and the Administration need to create new legal avenues to increase immigration

This study shows that Congress and the Administration have crucial decisions to make: create new legal avenues to increase immigration at all skill and family levels, or risk persistently high inflation in the years ahead.

Elected leaders must act now before inflation becomes a normalized feature of the U.S. economy. Failing to act—or worse, reducing immigration—would make it impossible for our economy to recover successfully from the pandemic, leaving it crippled by persistent worker shortages and sustained inflation for years to come.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that decreases in immigration exacerbate worker shortages and impact inflation

"...households in places like Phoenix or Tampa...faced inflation rates that were 2.5 percentage points higher than households in places like San Francisco and New York City..."

In 2020, millions of workers moved to virtual, at-home environments for their jobs. Remote work provided social distancing during the pandemic, but also enabled workers to relocate to new places in new states, far away from their previous physical office location. This led hundreds of thousands of people in 2020 to relocate—about twice as many than before the pandemic—often from major U.S. metros to smaller, more suburban, or more southern communities around the country.

As people relocated to new communities, they contributed to increasing demand for products and services, many of which were not as abundantly available in their new locations. And while many professionals were now working in new communities, there was a fundamental labor mismatch. These new residents were not doing the kind of work that was needed in these new communities to meet the increased demand, much less to fill labor shortages that already existed before they relocated.

With a high demand for services and a low supply of workers, prices rose in areas across the U.S.—not just for housing and other goods, but also for products that require a large number of service workers to produce them. Elevated demand in these areas drove up the cost of services, for anything from at-home healthcare and personal care services to restaurant dining and home repairs.

Mason researchers found households in places like Phoenix or Tampa—metro areas in the top quarter of movement within the U.S.—faced inflation rates that were 2.5 percentage points higher than households in places like San Francisco and New York City—metro areas in the bottom quarter of movement within the U.S. That translates into an increase of $1,500 in annual expenditures for the average American household that made this move.

Inflation rates were highest in areas that experienced some of the highest levels of new residents within the U.S. These same destinations were also the ones with more severe labor shortages, evidenced by higher job vacancy-to-unemployment rates as well as sharp wage increases.

Local inflation spikes could have been abated if immigrant workers had been available to fill many of the jobs in these new destination regions. In times of sudden economic shifts, immigrants provide a flexible workforce that can meet new demands in growing industries, particularly in industries that already rely on immigrant workers. The stark absence of hundreds of thousands of immigrant workers who did not enter the workforce before and during the pandemic made these new destinations even more unable to meet new, shifting demands.

In fact, Mason researchers found that labor shortages, a major driver of inflation, were sharp in industries that heavily rely on an immigrant workforce, as evidenced by wage spikes during the pandemic. This shows that the absence of immigrant workers was a particularly strong contributor to inflationary pressures, and that industries that rely on immigrants struggled the most. For example, the correlation between wage increases and the number of new residents was particularly strong in construction and leisure and hospitality, industries where immigrants make up about a fifth of the workforce.

Wage increases may, on the surface, seem like a good thing for American workers. And, in stable inflation conditions, this is often the case. But not during a time of rising inflation and perpetual worker shortages. The economy can begin an endless wage-price spiral, an economic condition in which wages increase because of a lack of workers and those wage increases are passed on to the consumer. In order to retain workers who see their wages adjusted for inflation falling, employers feel compelled to raise wages again, and this cycle repeats itself. One way out of the spiral, and to stabilize inflation, is to insert new workers into the labor force, moderating the role labor shortages are having on wages.

Within just a few months of coming out of the pandemic, local inflation and immigrant workforce shortages compounded into a national crisis. Come 2022, job openings at the national level skyrocketed. But with immigration returning to near pre-pandemic levels by 2022, worker shortages and inflation eased.

Recent immigration actions provide a limited preview of how increased immigration can tamp down inflation. Hundreds of thousands of immigrants have been paroled into the U.S. for humanitarian reasons since the start of the Biden Administration. Offering these individuals refuge is the right and moral thing to do, but this timely increase in immigration coming out of the pandemic simultaneously helped address labor shortages.

"On the aggregate, about a quarter of the decrease in job openings from 2022 to 2023 in industries with labor shortages can be traced to paroled immigrants working in the U.S. economy."

FWD.us estimates that about 450,000 individuals who were permitted to enter the U.S. via parole in 2021 and 2022 likely also ended up working in industries with labor shortages. On the aggregate, about a quarter of the decrease in job openings from 2022 to 2023 in industries with labor shortages can be traced to paroled immigrants working in the U.S. economy.

And the Administration’s new 2023 humanitarian parole policy for individuals from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela (CHNV), in addition to extending vital humanitarian benefits to people seeking safety, will certainly help ease worker shortages and thus inflation even further. Assuming paroled immigrants through the CHNV policy take similar jobs as co-nationals who entered the U.S. in recent years, FWD.us estimates some 170,000 of these paroled individuals will likely work in industries experiencing labor shortages.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many workers shifted to remote environments and relocated across the country. As communities began to reopen, the U.S. faced extraordinary labor shortages that drove inflation and consumer prices up. Our analysis shows that steep declines in immigration levels exacerbated the impact of increased relocation throughout the U.S. and contributed to increased inflation. Economic shifts during the pandemic illustrate what lies ahead for the United States if Congress does not reform the U.S. immigration system.

The U.S. working-age population will only increase with immigration

“Under a zero-immigration scenario where immigration stopped for the next two decades, the U.S. working-age population would shrink 11% by 2040. And under a low-immigration scenario, the U.S. working-age population would remain relatively flat.”

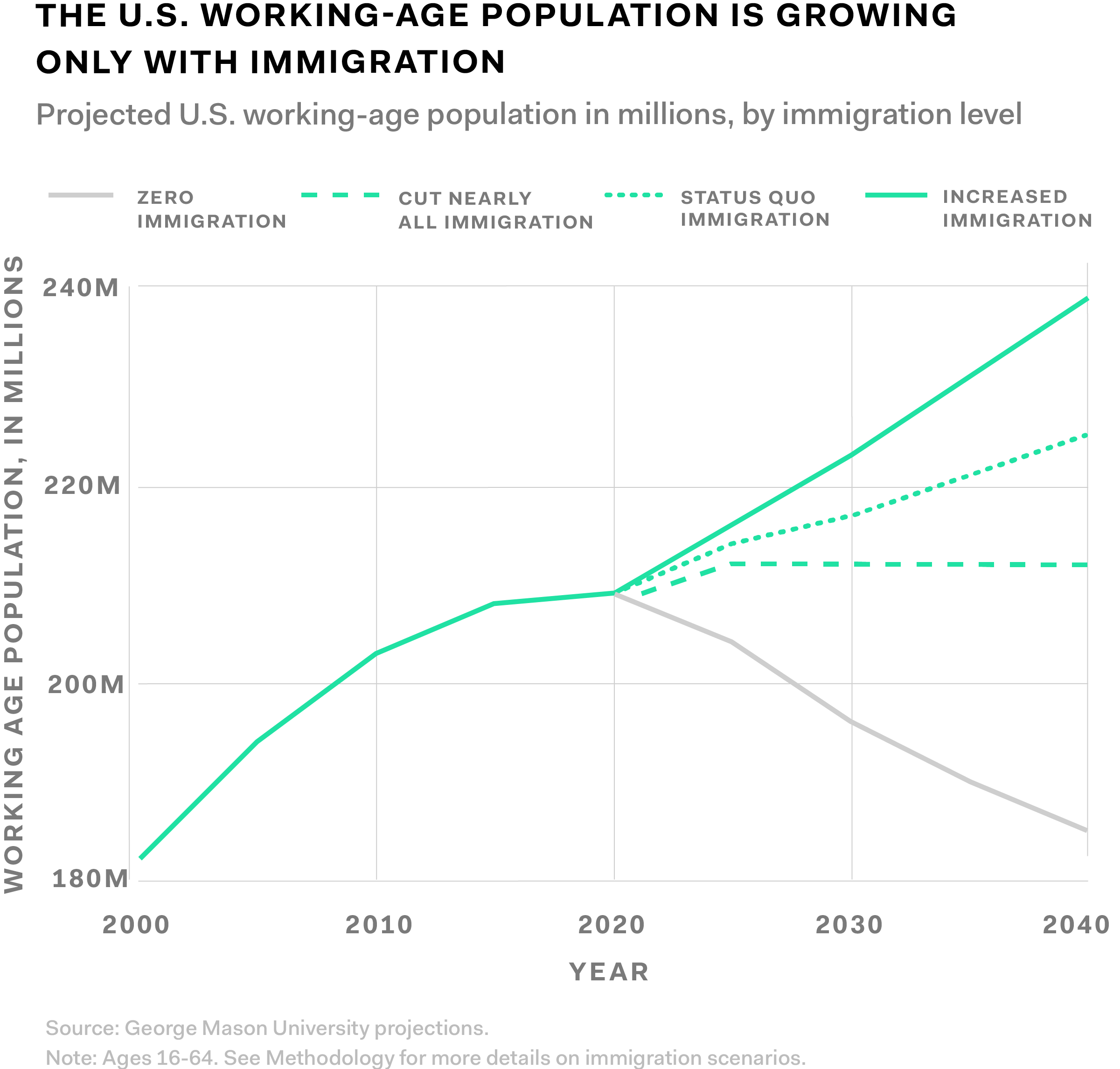

Recent months’ worker shortages are only a preview of the economic disaster that could occur in the years ahead without Congress passing more commonsense immigration policies. Demographic projections prepared by Mason researchers show how our working-age population, those aged 16 to 64 years, is now growing only through immigration.

Demographers applied four immigration scenarios to population projections, including: (1) cutting nearly all immigration, or those seen during the pandemic, (2) status-quo levels, or about those we are experiencing now as well as a couple of years before the pandemic, (3) increased levels, or 50% more than status-quo levels, and (4) zero immigration. (See our Methodology for a more detailed description of immigration scenarios).

Under a zero-immigration scenario where immigration stopped for the next two decades, the U.S. working-age population would shrink 11% by 2040. And under a low-immigration scenario, the U.S. working-age population would remain relatively flat. Both these scenarios, leave the working-age population at a level that our economy cannot sustain, now during a period of labor shortages and for the long term as a significant share of the population continues to age and heads into retirement.

By contrast, if immigration levels were to remain the same as they were a few years before the pandemic and about where they are today – or the status quo immigration scenario – the working-age population would marginally grow about 6%, or roughly 10 million people, by 2040. For perspective, the current job opening rate is about 6%, reflecting nearly 10 million unfilled jobs.

But the U.S. economy needs new workers now. With record low unemployment, businesses are desperate to hire more employees to meet vital workforce needs. Additional workers cannot be found in our current working-age population. Labor force participation rates for the current workforce have remained stubbornly stable for the past year, indicating that the current U.S. population that is out of the workforce is not a realistic source for new workers in the short or medium term. Research indicates that hundreds of thousands of workers left the U.S. workforce during the pandemic and are not coming back. Many more have reduced the number of hours they are working. These open jobs cannot simply be filled by teenagers looking to enter the workforce early or seniors already in retirement. More workers are needed to meet the shortfall.

Moreover, the era of worker shortages does not appear to be ending anytime soon. For instance, Congress has passed aggressive investments in infrastructure, legislation addressing climate change, and a bill jump-starting semiconductor manufacturing. But without more immigration, many of these investments will be stymied. And, as labor shortages in the past two years have already shown us, the U.S. risks sustained inflation if Congress does nothing legislatively on immigration to prepare for this additional job creation.

The best growth strategy for the U.S. economy and the U.S. workforce to close the immediate labor shortage gap and drive down inflation in the years ahead is to increase immigration. Raising immigration levels by 50% would increase the projected U.S. working-age population by about 13% by 2040—which would provide for current and growing labor needs, while also further expanding the U.S. economy. Doing so would keep our workforce growing at the rate it has for the past two decades. Doing anything less would lead to slowing growth.

Americans stand to benefit personally if Congress increases immigration levels

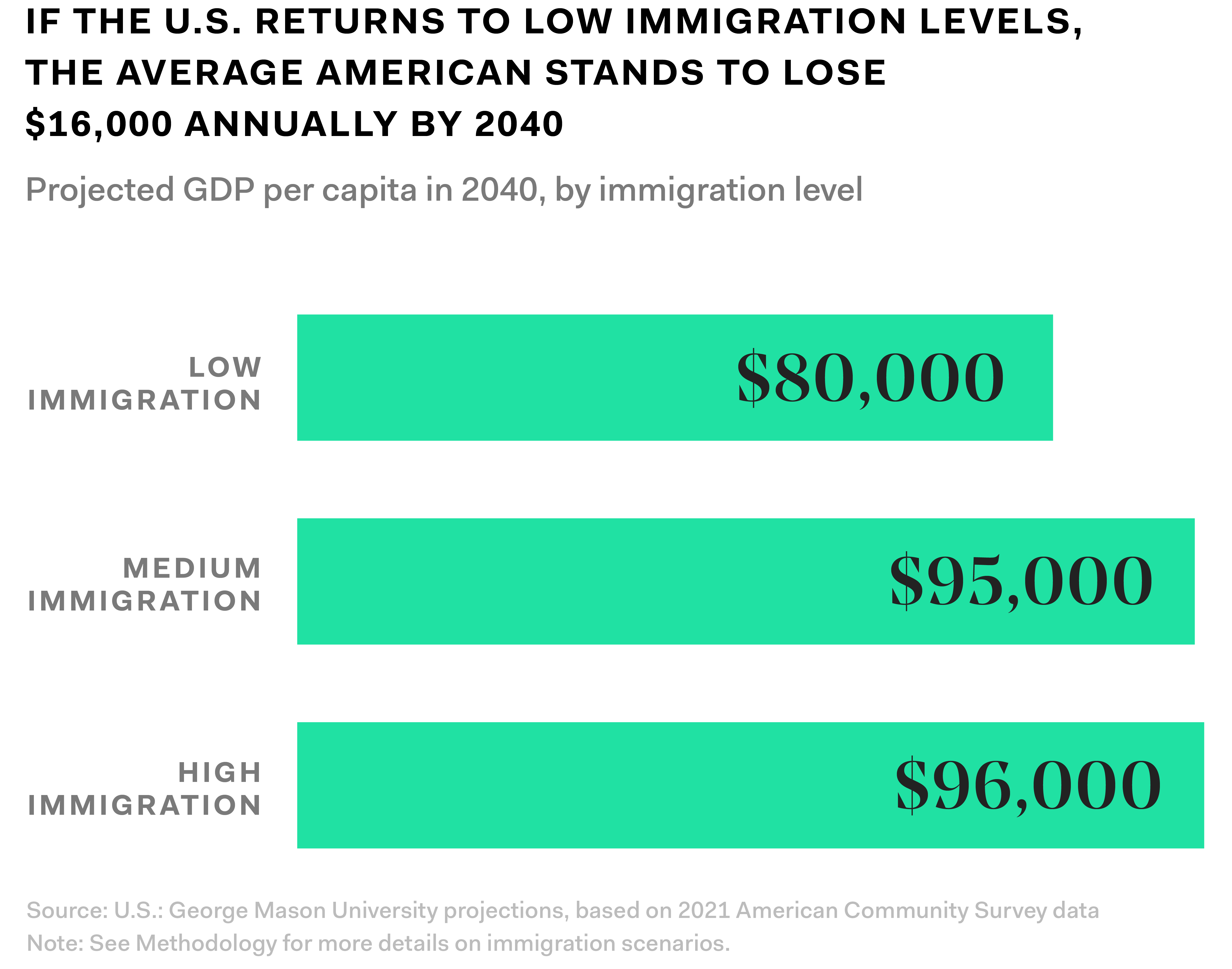

“GDP per capita is projected to increase by only about 19% during the next two decades, or about $16,000 less annually come 2040, under a low-immigration scenario.”

When the U.S. economy grows with increased immigration, all Americans stand to benefit. A growing economy increases productivity and eases inflation, but also raises real wages for everyone.

Positive growth in the immigrant labor force, which also represents positive growth in the American workforce, is a win-win for all. Compared with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in 2020, keeping immigration levels as they are or increasing them by half will lead to an increase of some 40% in GDP per person by 2040, according to the FWD.us study in collaboration with Mason researchers.

Economic projections show an even greater financial bonus for everyday Americans, thanks to increased immigration: individual GDP, on average, would be $1,000 greater in 2040 if the U.S. increased immigration levels by 50% in the years ahead. This is because an increase in immigrants will grow the labor force beyond its current level, simultaneously expanding the entire U.S. economy, and permitting everyone to benefit from that expansion.

With increased levels of immigration, inflation will ease as worker shortages lessen. Consequently, raising immigration would solve immediate and longer-term labor demand issues, while allowing for a growing economy, enabling all workers to share in real wage growth rather than wages responding to rising inflation.

However, these economic gains for Americans would be significantly diminished if immigration levels were returned to low or pandemic levels. GDP per capita is projected to increase by only about 19% during the next two decades, or about $16,000 less annually come 2040, under a low-immigration scenario. With lower immigration, the labor force would stay about the same size or even contract, stagnating economic growth and leaving a smaller economy for everyone.

Personal economic gains associated with increased immigration show that immigration spurs a growing economy, benefiting U.S. residents of all backgrounds. Congress should not stand on the sidelines on this potential economic boom for American taxpayers. Instead, it is clear that pro-immigration policies will make most everyone economically better off.

Congress and the Administration are responsible for passing legislation that increases immigration to drive down inflation and build a stronger economic future

“Congress and the Administration need to address these immediate and longer-term workforce challenges by working together on bipartisan legislation to modernize our immigration system.”

As this report makes clear, increasing immigration would benefit the U.S. significantly in many ways. Congress cannot instantly set the immediate trajectory of immigration, however. For some policy proposals, it may take years for new laws to produce meaningful impact. That is why Congress must act now to be able to see a turnaround for our workforce in the years ahead.

Fighting inflation and reversing demographic trends will require addressing workforce shortages, building strong talent pipelines, and welcoming more permanent immigrants to communities facing decline. Accordingly, FWD.us recommends several possible avenues for legislation to expand immigration pathways, including modernizing legal immigration levels, creating a direct pathway to permanent residency for STEM international students, and creating targeted regional programs to help ensure that every state and community can share in the economic and workforce benefits of immigration.

Meanwhile, the Administration should continue to expand legal avenues for people seeking relief in the U.S., including extending Temporary Protected Status for individuals from countries for which returning would be very unsafe. The Administration should also continue working to expand avenues for highly educated and skilled workers, particularly with STEM skills, to fill critical job openings in emerging industries like A.I. and advanced manufacturing. All these Administrative measures would enable a greater number of immigrants on the sidelines of the U.S. workforce to immediately enter the labor market and address current labor needs.

Making these changes now will produce the greatest benefits, before an aging population and a lack of workers make rising inflation and labor shortages a permanent feature of our economy. During the pandemic, we saw how a slowdown in immigration can have disastrous effects on the U.S. economy. We cannot wait any longer to see another period of sustained inflation without sufficient wage increases. By then, the economic challenges will be far too great, and the policy shifts all the more difficult to implement and support.

Congress and the Administration need to address these immediate and longer-term workforce challenges by working together on bipartisan legislation to modernize our immigration system.

The inflation study relies on data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics. The number of Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) shown are limited by the data points available for inflation. Inflation is measured as the rates for 2022 over 2020.

The inflation study was conducted by Justin Gest, George Mason University and R. Andrew Butters, Indiana University.

Immigration parole methodology can be found here.

Population projections rely on the cohort component method used by the U.S. Census Bureau and other demographic research organizations. Projections are long-term forecasts based on what we know about populations today and projecting those trends into the future. They allow for different assumptions—like varying immigration rates—to lead to different projected outcomes.

In this study, baseline population data were drawn from the 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) by age, sex, race, and place of birth (U.S.-born, foreign-born). Projections rely on trends for national mortality and fertility rates from 1990 through 2019. (2020 was avoided because of an unusual year for both mortality and fertility due to the pandemic).

People both enter the U.S. (immigrants) and leave the U.S. (emigrants). The combined effect leads to a net migration rate, with a positive rate indicating more people entering than people leaving. Different levels of immigration were calculated while keeping emigration constant across all scenarios. The study uses constant net migration rates tied to the broader U.S. population. Consequently, the actual number of immigrants projected to enter the U.S. changes year to year, depending on the immigration scenario level.

The study considers four immigration scenarios, based on immigration levels in 2017:

- Zero immigration—no immigration.

- Cut nearly all immigration—pandemic, or 50% of prepandemic (2017) levels, or roughly 600,000 immigrants entering the U.S. annually

- Status quo immigration—prepandemic (2017), also similar to current immigration levels, or roughly 1.2 million immigrants entering the U.S. annually

- Increased immigration—50% more immigration than prepandemic (2017) levels, or roughly 1.8 million immigrants entering the U.S. annually

The resulting population growth was estimated for each immigration scenario, keeping other population dynamics constant. Population projections for the working-age population are for ages 16 to 64.

Economic growth, or real GDP, is based on population projections for demographic groups using economic data from the 2021 ACS, and established economic projection modeling from previous studies. These economic projections for GDP per capita, referred to as wages in this report, do not take into account sudden economic shocks, slumps, or recoveries. Economic growth is expressed as GDP using constant 2021 U.S. dollars.

The population projections study was conducted by Justin Gest, George Mason University; Erin Hoffman, Utah State University; Annie Hines, University of California, Davis; and Ethan Sharygin, Portland State University.

Tell the world; share this article via...

Get Involved

We need your help to move America forward. Learn what you can do.