Research shows that increasing prison sentences and length of stay is costly, grows the prison population, and does not improve public safety.

Research has consistently demonstrated that long sentences do not improve public safety. More severe sentences do not deter individuals from committing crime in the future, nor reduce recidivism for those who serve them. In fact the “certainty” of punishment (that is, the certainty that an individual committing a crime will be caught and punished) is much more important to preventing future crime than the severity (the intensity of the punishment, including the length of time someone spends in prison).5

Research has also found that locking people up for drug offenses for longer periods of time does not reduce drug availability in the community. People sentenced to prison for distribution are easily replaced in drug markets, and many are users themselves who only sell to support their own addiction. Several United States Sentencing Commission reports have found that releasing individuals convicted of drug crimes from prison early led to no difference in their recidivism rates.

On the other hand, increasing time served requirements has been linked to reductions in participation in programs in prison and an increase in recidivism, in addition to increases in the prison population.

Some proponents of minimum time served requirements argue that the prison population impact will be offset by prosecutor’s seeking shorter sentences. However, research and case studies of states that enacted time served requirements have consistently shown substantial growth in their prison populations, while sentence lengths largely remain the same. These states that enacted “truth-in-sentencing” statutes, requiring some or all people in prison to serve a certain minimum percentage of their sentence behind bars, had prison populations 13% larger than other states. No other policy change contributed more to prison growth. This is especially true for states, such as Mississippi, Ohio, and Arizona, that enacted minimum time served requirements for all felonies as the Council’s proposal recommends.

Minimum Time Served Requirements in Other States

In 1995, Mississippi passed a law establishing minimum time served requirements for all felony offenses. The new requirements led to a 52% growth in the prison population by 2001 and a 24% increase in the average length of stay for people with nonviolent offenses, even as average sentence lengths decreased. By 2000, Mississippi’s prison population was 37% larger than was originally projected before implementing mandatory time served requirements.

In 1994, Arizona passed truth-in-sentencing laws that established minimum time served requirements for all offenses. From 2000 to 2018, Arizona’s prison population grew by 60%, despite falling crime rates. The state now has the 5th highest imprisonment rate in the U.S and currently spends over $1 billion dollars on corrections each year, an increase of $280 million annually from 2000.

In 1997, Ohio enacted SB 2, which established determinate sentencing ranges that created minimum time served requirements for all offenses. Initially, Ohio’s prison population decreased, likely due to SB 2’s enactment of sentencing guidelines that required a judicial fact-finding process before a harsher sentence could be imposed. However, these guidelines were made merely advisory following state court decisions in 2006. Soon after, Ohio’s prison population shot up. By 2008, Ohio’s prison population was rapidly growing, largely driven by increased average lengths of stay. From 2005 and 2015, Ohio had the 7th fastest growing prison population in the nation.

Conclusion

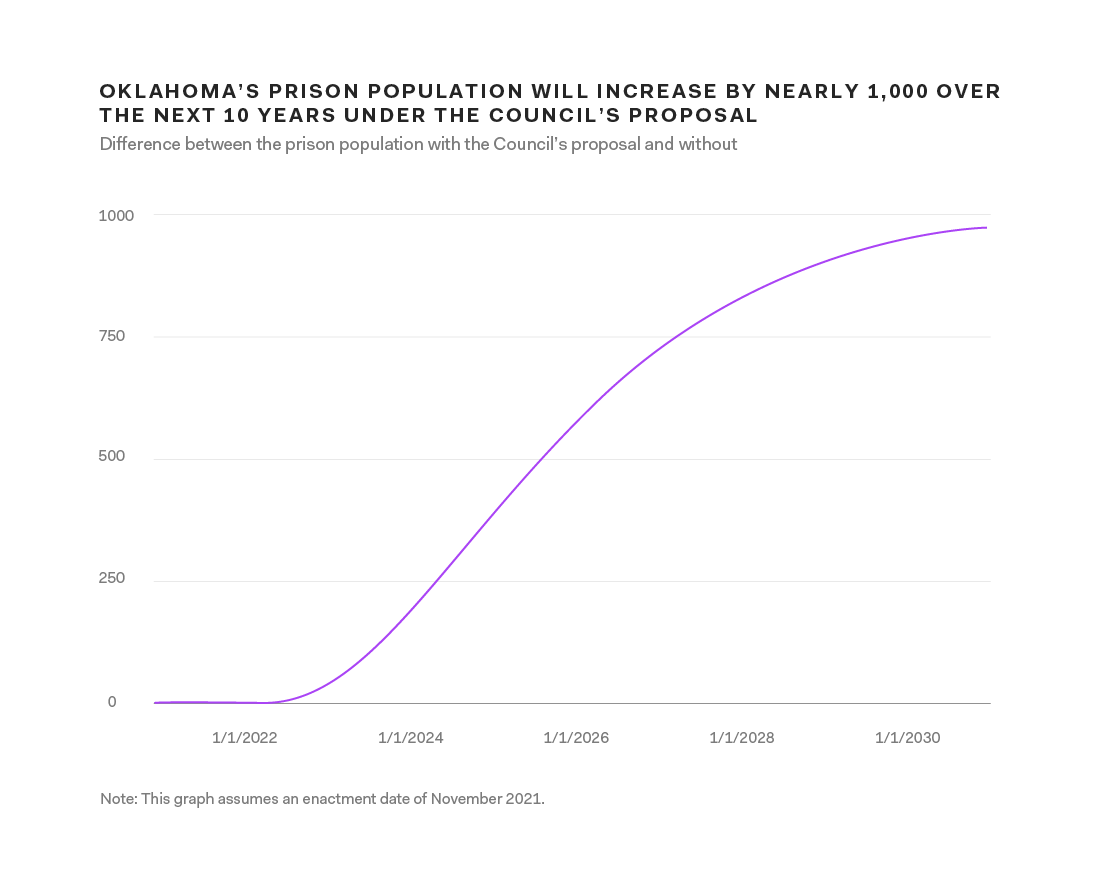

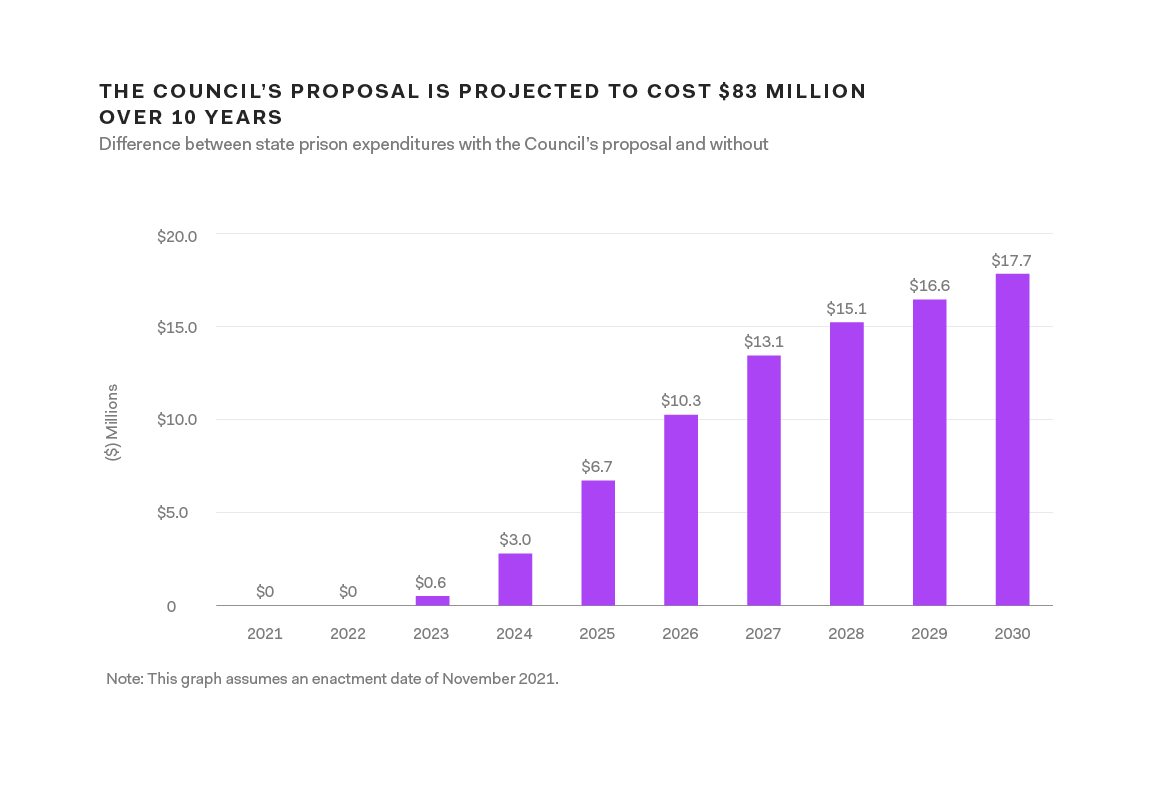

Data shows that Oklahomans currently serve substantially longer prison terms than people in other states, particularly for nonviolent drug and property offenses. The Council’s latest proposal would increase Oklahoma’s prison terms, leading to almost 1,000 more beds and additional prison expenditures between $20 million and $83 million over a 10-year period. This increase in Oklahoma’s prison population is driven by the imposition of minimum time served requirements across felony classes.

There is substantial research showing a strong relationship between minimum time served requirements and longer prison terms and larger prison populations. Our findings suggest Oklahoma is no different.

Future recommendations by the Council must be consistent with its statutory mandate to “reduce or hold neutral the prison population” in the state. True criminal justice reform can and should go further: safely and smartly reducing the prison population and saving taxpayer dollars that can be reinvested into priorities that will make Oklahoma a safer and stronger state, such as victim services and mental health and drug treatment.

Methodology

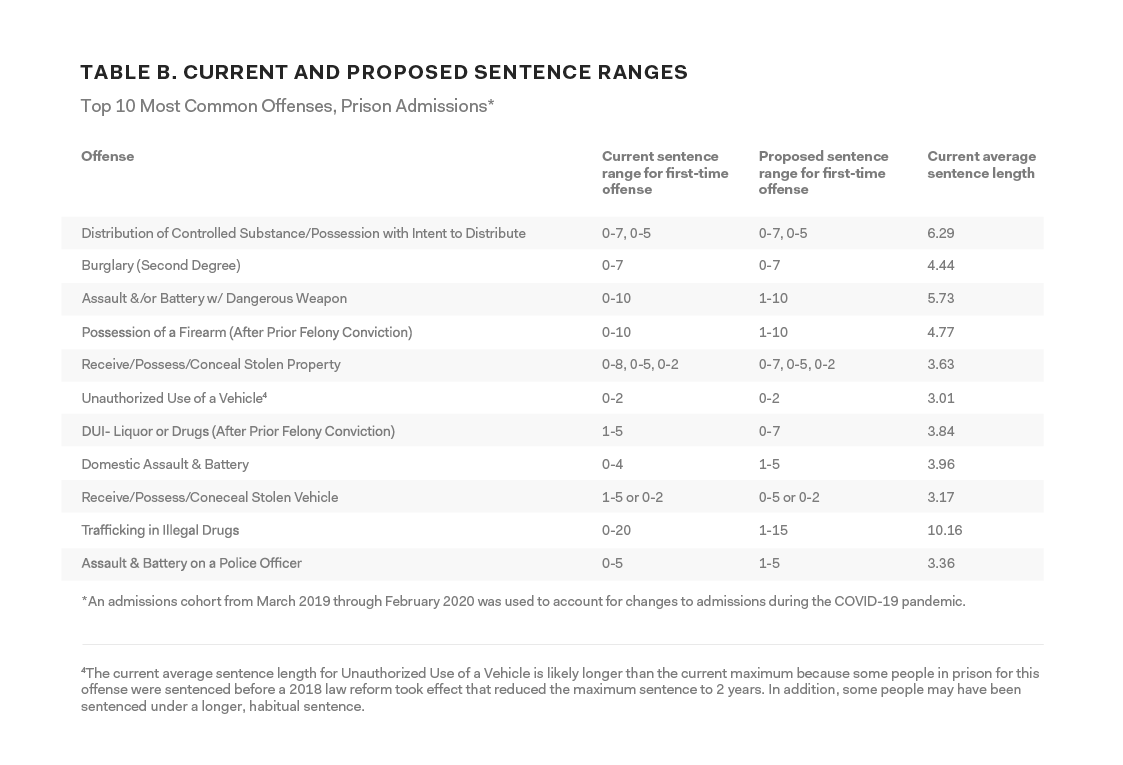

The data used in this report was individual-level data from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections in FY 2019 and FY 2020. Admissions data after March of 2020 was not included due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on prison admissions. Our sample analysis draws from the top 50 most common offenses in Oklahoma’s prison system, equivalent to approximately 90% of all prison admissions per year. We used this data to individually calculate the number of people per offense who would have longer or shorter stays in prison if these recommendations were adopted and the degree to which their time served in prison would increase or decrease. Our analysis adjusted for the number of counts an individual is serving in prison.

Baseline

To predict Oklahoma’s prison population under the Council’s 2021 proposal, we first created a “baseline” prison population projection. This is an estimate of how the prison population would grow over the next 10 years with no changes in the law. The baseline projection accounts for recent trends in Oklahoma prison admissions, sentence lengths, and length of stay in prison. Because of recent changes in criminal justice policies, as well as a reduction in prison admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic, this projection relies mostly on prison admissions in Oklahoma from March 2019-February 2020 and prison releases from FY 2019 and FY 2020, with adjustments for recent reforms that have not yet been fully implemented. It also looks at the remaining sentence lengths for people currently in prison, as well as their age, to estimate how long they will remain behind bars. This baseline assumes that after the COVID-19 pandemic ends, prison admissions will return to their pre-pandemic levels and there will not be a surge in admissions because of a backlog of cases. If there is a surge of prison admissions, prison population growth may be significantly higher than projected in the next few years, absent further reform. The baseline provides a counterfactual to compare to the projected prison population under the current sentencing structure.

Impact of the Council’s Proposal

We then calculated the impact the Council’s new penalties would have on the 50 most common crimes in Oklahoma’s prison system, accounting for approximately 90% of all people admitted to prison. People who are newly sentenced to prison (on a month-to-month basis) would be in prison longer, on average, if the state adopted the Council’s proposal. These calculations factor in the following changes:

- Newly added minimum time served requirements for all non-”85% offenses,” based on the number of priors.

- A decrease in time served requirements for some “85% offenses.”

- A decrease in sentence maximums for certain offenses currently eligible for life under the habitual offender statute where the enhanced maximum was significantly decreased.

These changes are assumed to be applied prospectively, meaning only to individuals who have not yet been committed or sentenced for their crimes. If the Council’s recommendations were to be applied retroactively (to everyone currently in prison), the impact could be substantially different. For instance, 50.2% of people currently in prison were sentenced for an 85% crime, a much larger group than when looking at new admissions. However, retroactive application of these requirements would entail a complicated recalculation of every individual’s eligibility for release, and thus would be difficult to implement.

This model assumes that the changes go into effect in November 2021, although significant impact on the prison population is not seen in the first year after enactment because the primary driver of the change is adding on additional months at the end of the time each person spends in prison. If the proposal was put into effect at a later date, the overall impact would stay the same, but would just be shifted backward in time.