FWD.us Estimates Show Immigrant Essential Workers are Crucial to America’s COVID-19 Recovery

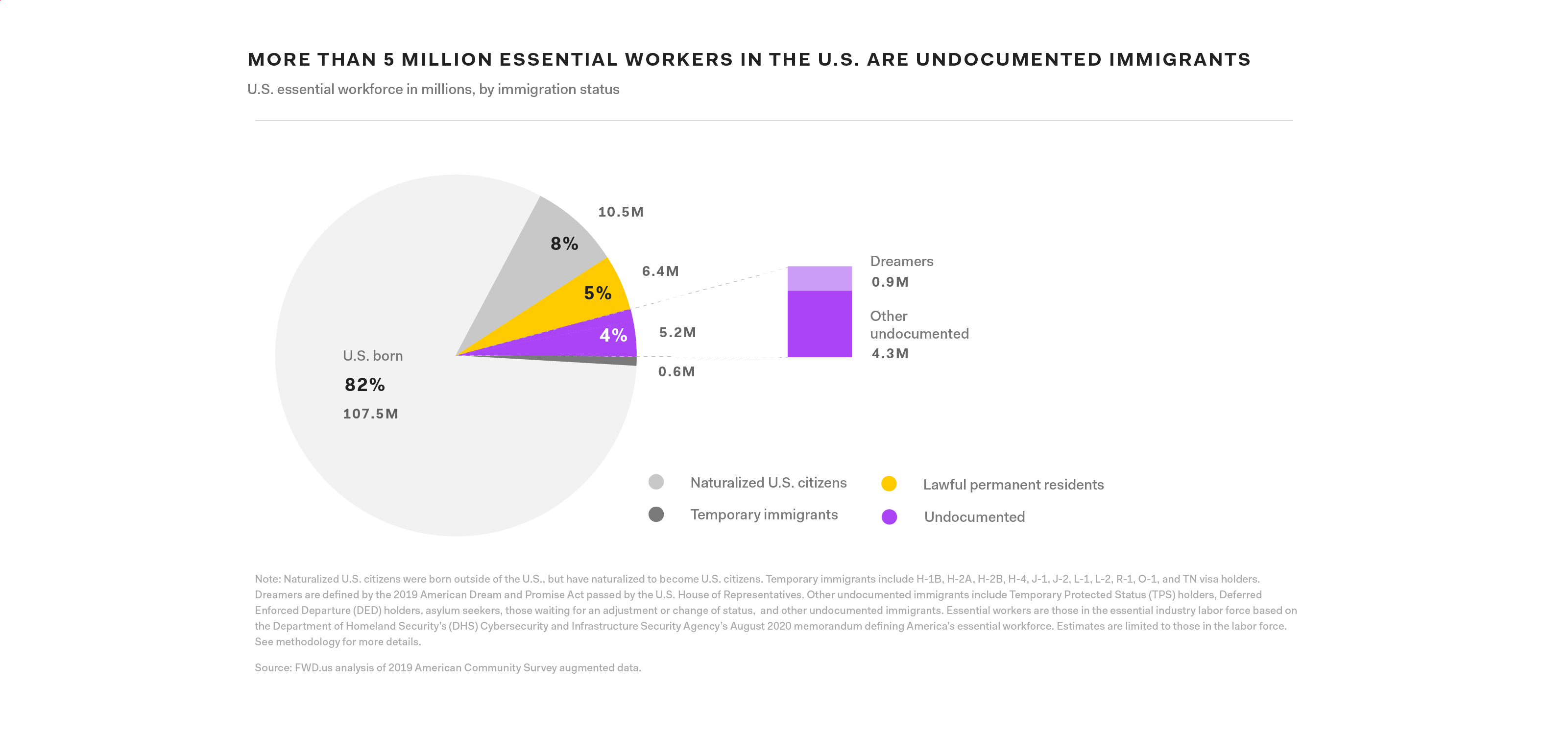

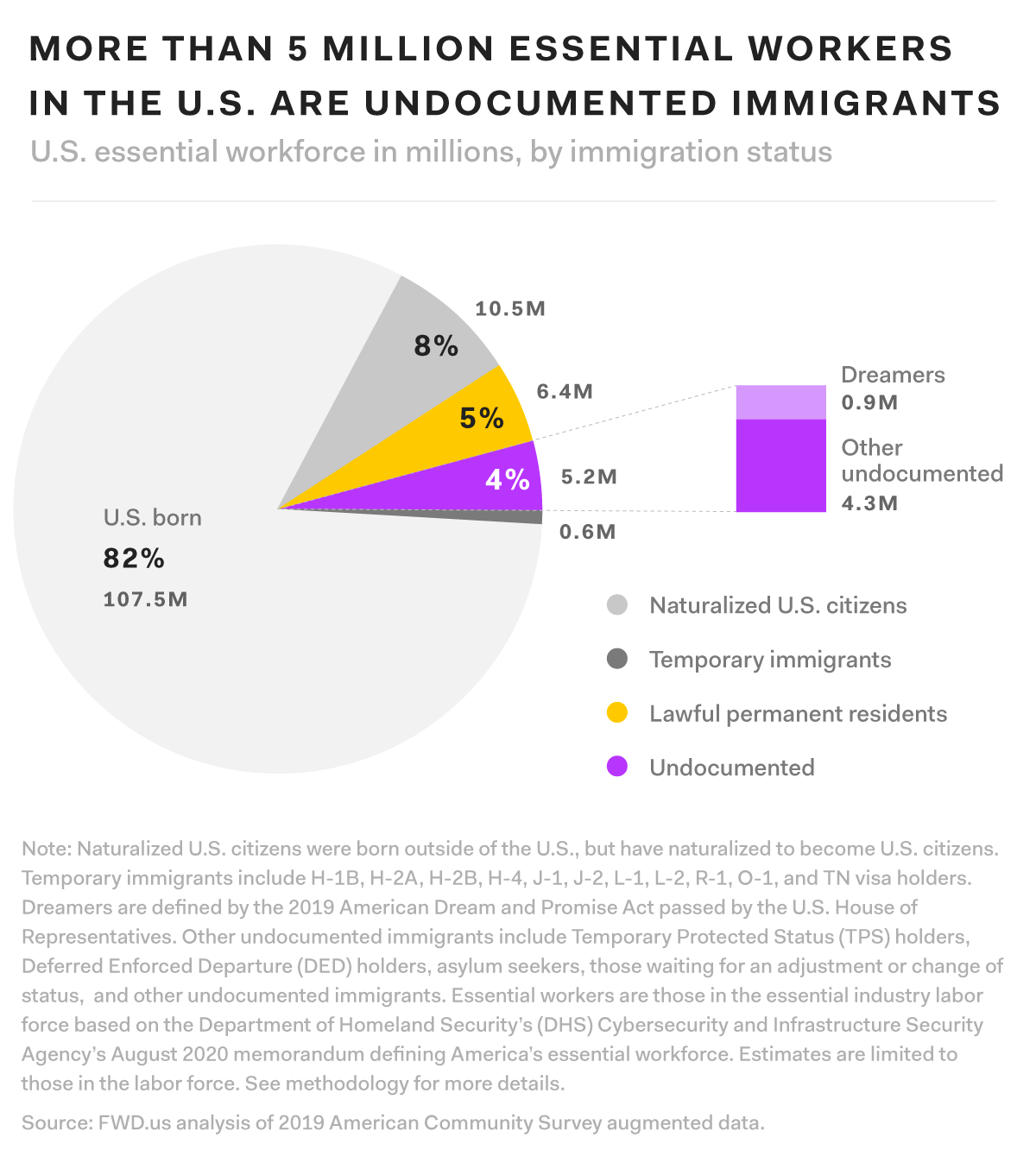

New estimates from FWD.us show that immigrants represent a substantial, and thus critical, part of America’s essential COVID-19 workforce combating the pandemic. Numbering nearly 23 million people, these medical, agricultural, food service, and other immigrant essential workers make up nearly 1 in 5 individuals in the total U.S. essential workforce.

Undocumented immigrants are one of the largest groups among the immigrant essential workforce, making up 5.2 million essential workers, of which nearly 1 million are Dreamers part of the 2019 American Dream and Promise Act who entered the U.S. as children. With relatively low unemployment in many essential sectors, the loss of the undocumented immigrant essential workforce would be particularly crippling for future COVID-19 economic recovery. Similarly, failing to address the lack of legal status of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. could endanger their lives, as well as the health and lives of Americans who rely on these essential workers every day. Importantly, it is also a moral failure to call undocumented immigrants “essential” while failing to provide them with legal status.

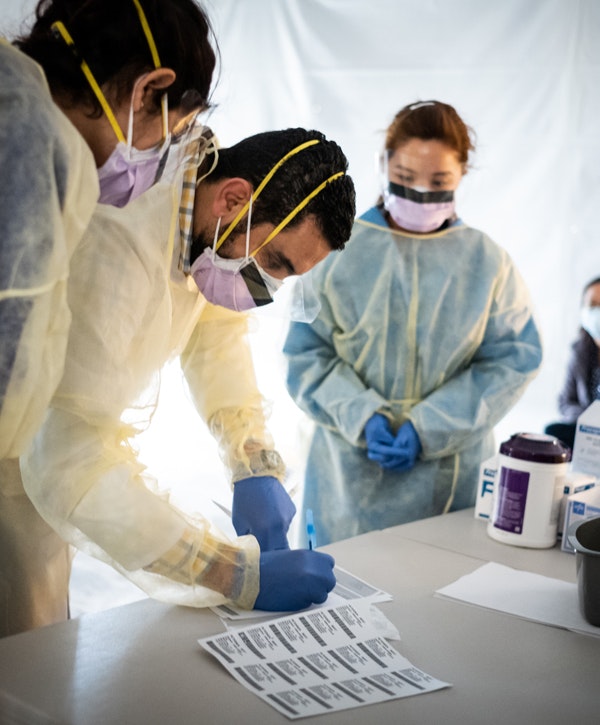

As more than two-thirds of all undocumented immigrant workers serve in frontline jobs in essential industries—a considerably higher share than among other immigrant groups or those individuals born in the U.S.—undocumented immigrants have been more likely to contract COVID-19. These frontline workers could not perform their essential jobs from home, and many have been hospitalized; thousands have died. Despite this, undocumented immigrants have continued to work on the front lines, delivering home healthcare services, cleaning medical facilities, building temporary hospitals and clinics, and other essential services. Also critical are the estimated million-plus farmworkers part of the 2019 Farm Workforce Modernization Act providing food to America’s tables during the pandemic.

At the same time, undocumented immigrant essential workers live in well-established families, with most having lived in the U.S. for more than a decade, as well as living with millions of U.S. citizen household members. Additionally, the earnings of most families with undocumented immigrant essential workers are twice the poverty level.

Undocumented immigrant essential workers, and other individuals living with temporary status, face an uncertain future in the United States, particularly given the onslaught of executive orders and policy changes made by the outgoing Trump Administration. Some essential workers have temporary nonimmigrant visas or limited protection from deportation like DACA or TPS, while most have no legal status at all.

Immigrant essential workers are indispensable; the United States continues to rely on them to fight the pandemic and contribute to a long-term recovery. Consequently, they should not be subject to deportation, but instead should be provided certainty over their future in the United States. By doing so, we would recognize the critical work that millions of immigrant essential workers perform every day, and thus secure all our futures.

Congress must include ALL essential workers, including lawful permanent residents, immigrants with temporary status, and undocumented immigrants in future COVID-19 legislation. This includes creating lawful permanent residence pathways for ALL immigrant essential workers, regardless of their immigration status. Given their personal sacrifice during the pandemic, it is the least Congress and President-elect Biden can do in helping them fight the pandemic alongside all Americans.

Immigrants are a critical part of America’s essential workforce

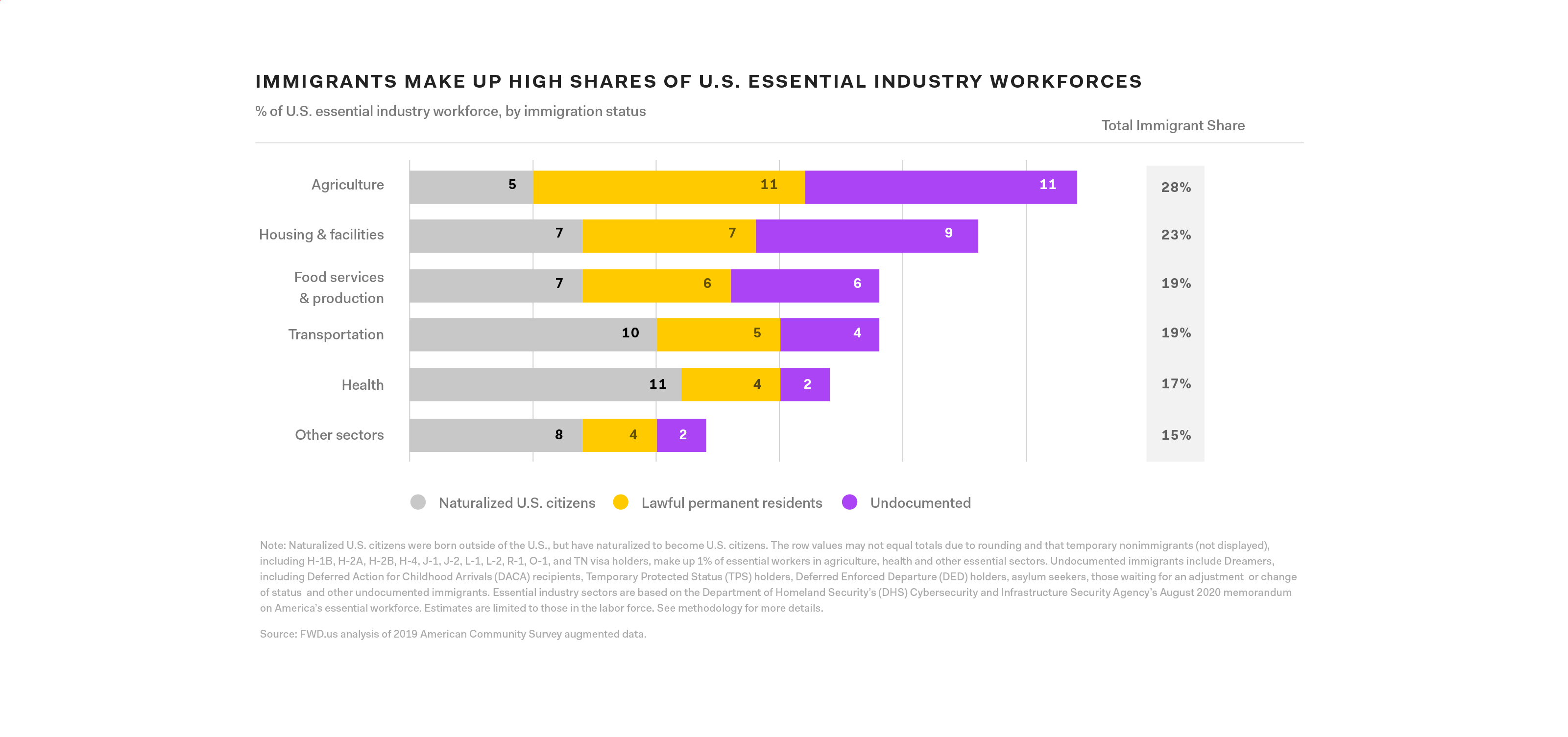

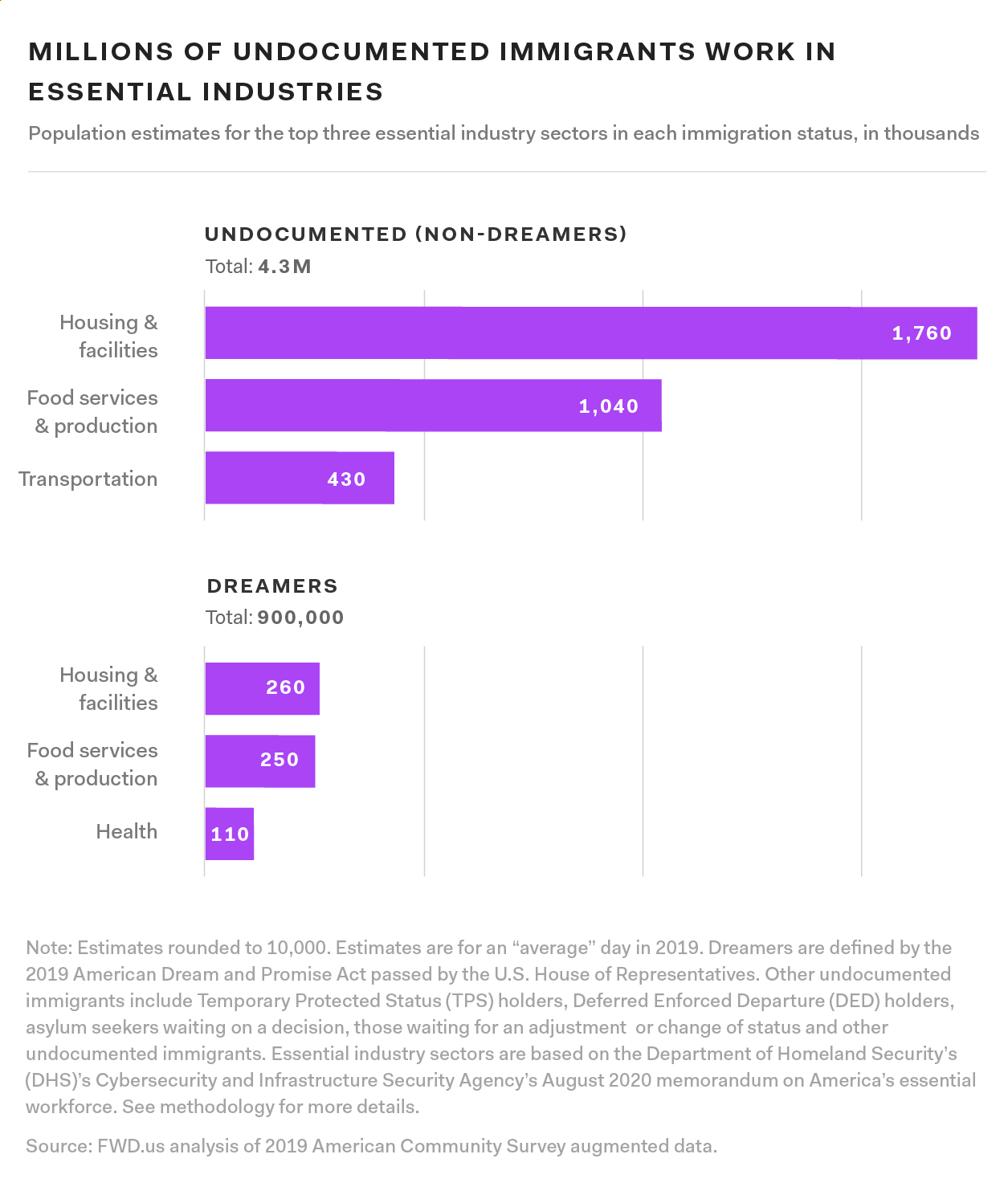

Immigrants make up a critical part of the American essential workforce, consisting of nearly a fifth of all essential workers in the United States, according to new estimates from FWD.us.1

In particular, undocumented immigrants make up more than 1 in 20 of America’s combined agricultural, housing and facilities, food services, and health essential workforce. For example, some 400,000 agricultural workers2, 400,000 cleaning staff; 300,000 packers, stockers, and shippers of essential goods; and 100,000 home health and personal care aides are undocumented immigrant essential workers.

Undocumented immigrant workers fill critical job openings that are not always filled by U.S.-born workers. In October 2020, for example, unemployment rates in several of these essential industries, including health (3.9%), agriculture (4.3%), and housing and facilities (5.7%), were near full-employment levels, despite the current economic climate.3 Many undocumented immigrant essential workers have worked in these essential industries for years, offering valuable and hard-to-replace skills that are critical in battling the COVID-19 pandemic.

And, as COVID-19 cases have increased dramatically in recent weeks for northern Midwest states such as Wisconsin, North Dakota, and Michigan, immigrant essential workers as a whole number some 7.6 million workers in the Midwest4, of which 1.6 million are undocumented immigrant essential workers. These medical professionals, food service clerks, and agricultural workers, among others, in these states are crucial during this pandemic peak.

“More than 1 in 20 of America’s combined agricultural, housing, food, and health essential workforce are undocumented immigrants.”

Immigrant essential workers have risked their personal health and that of their families in providing essential services. Immigrants are generally at higher risk of contracting COVID-19, in part because a larger share of immigrant workers (55%) than the U.S.-born (48%) have frontline jobs outside of the home in essential industries, with an even larger share among undocumented immigrant workers (69%). In fact, FWD.us estimates that immigrants have been 50% more likely to contract the virus than those born in the U.S.5 Essential workers on the front lines of the pandemic face an increased probability of exposure, as social distancing is not always possible and personal protective equipment may not always be available.

Immigrant essential workers contribute substantially to the U.S. economy. In 2019, immigrant essential workers are estimated to have had a combined $860 billion of spending power—disposable income—after the payment of up to $239 billion in federal and payroll taxes, and an additional estimated $115 billion in state and local taxes.6 Undocumented immigrant essential workers alone had an estimated $144 billion of spending power after the payment of up to $48 billion in federal, state, and local taxes.

Definitions

Essential workers are those in industry sectors deemed essential by the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) in its August 2020 memorandum7. An additional way to refine the essential worker population is to break down those working in essential industries into frontline workers versus those who can work from home.8 Most figures in this report use the broader essential industry definition when describing essential workers. The subset of frontline workers is used only for noting COVID-19 infection rates.

Immigrants are defined as foreign-born persons.9 Naturalized U.S. citizens were born outside of the U.S., but have become U.S. citizens. Lawful permanent residents are those living in the country on a long-term basis with “green cards.” Nonimmigrants—or immigrants with temporary status—generally live in the U.S. on a shorter-term basis, for one or more years. For this report, these immigrants include the following visa holders in the labor force: H-1B (specialty occupation professionals), H-4 (spouses and children of H-1B holders), J-1 and J-2 (exchange visitors), L-1 and L-2 (intracompany transferees), O-1 (individuals with extraordinary ability or achievement), R-1 (religious workers), and TN (NAFTA professionals) nonimmigrants. Seasonal immigrants are nonimmigrants with H-2A and H-2B annual work visas.

Undocumented immigrants consist of immigrants susceptible to deportation, whether they entered the U.S. unlawfully or overstayed a visa.10 The undocumented immigrant population also includes several groups currently protected from deportation, but whose long-term status is precarious. Consequently, these groups are considered undocumented immigrants. Among them are Dreamers, including Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, Temporary Protected Status (TPS) holders, Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) holders, asylum seekers waiting for a decision, and immigrants without lawful status waiting for an adjustment or change of status.

Millions of temporary, seasonal, and undocumented immigrant essential workers face an uncertain future in the U.S.

In all, nearly 6 million essential immigrant workers do not have certainty about their future ability to reside in the United States. Some are working in the U.S. as temporary workers, while others have a protected status. Still others, however, have no lawful status.

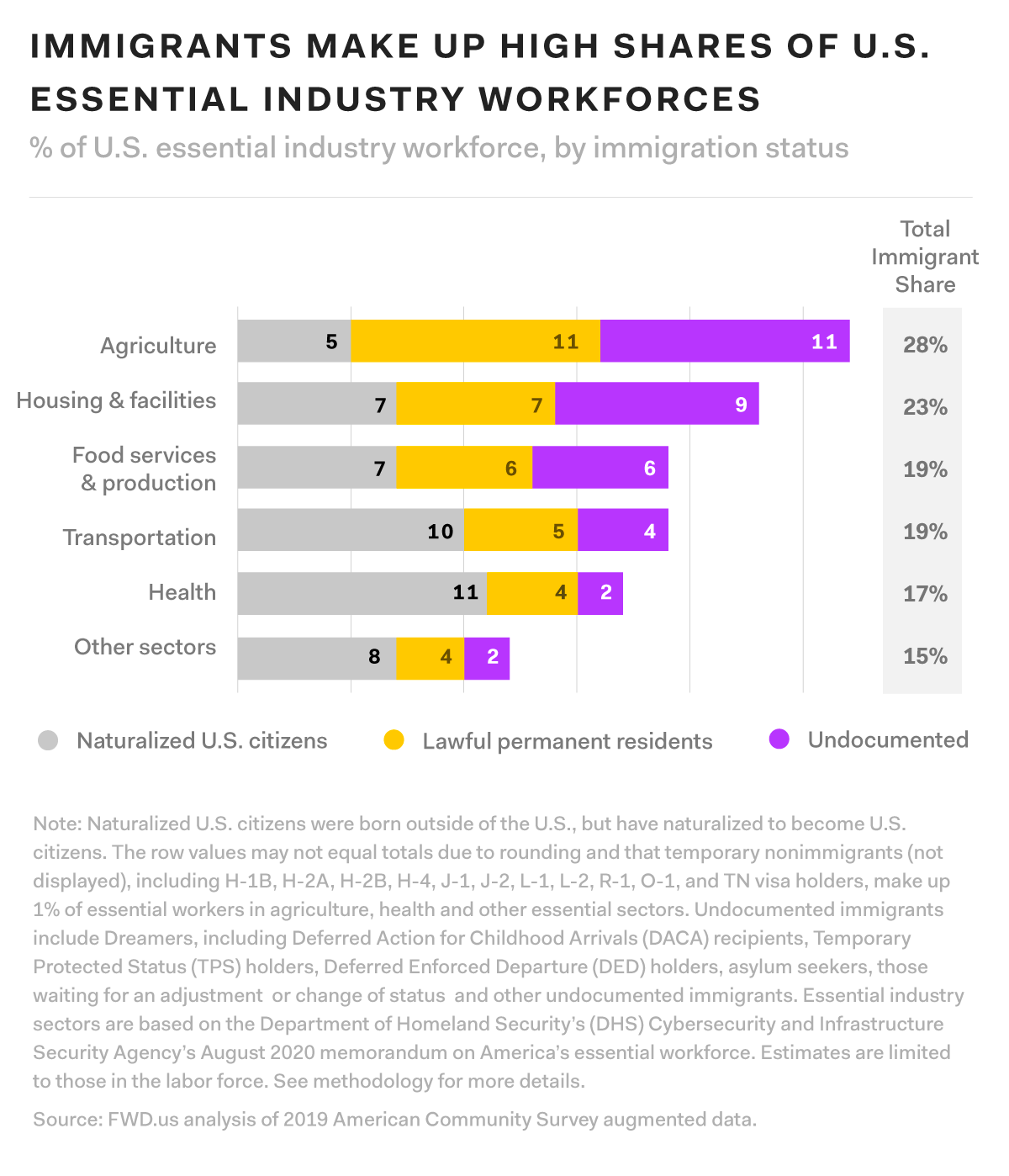

Nonimmigrant temporary workers with H-1B, H-4, J-1, J-2, L-1, L-2, O-1, R-1, and TN visas work in various skilled and professional occupations, with many holding visas for one to three years, but with limited opportunities for renewal. Estimates show that nearly half a million immigrants with temporary status work in essential industries, including 160,000 in essential telecommunications, information technology, and financial fields. An additional 130,000 provide medical services, including 30,000 physicians and 20,000 life scientists. And 70,000 provide educational services, including 20,000 professors. Although these temporary immigrant essential workers live lawfully in the U.S., their temporary visas are subject to renewal and not always guaranteed, especially given the changing legal landscape of nonimmigrant visas.

Seasonal nonimmigrants working in essential industries, such as those on H-2A and H-2B visas, number about 40,000 people in food services and production, 30,000 in housing and facility services, and 20,000 in agricultural production. Although their visas are at the most a year in length, many return each year—or have their status renewed stateside—to provide this essential work. Estimates are that some 90,000 seasonal nonimmigrants work in essential industries.11

“Nearly 6 million temporary, seasonal, and undocumented immigrant essential workers deserve immigration protections to live and work legally in the United States.”

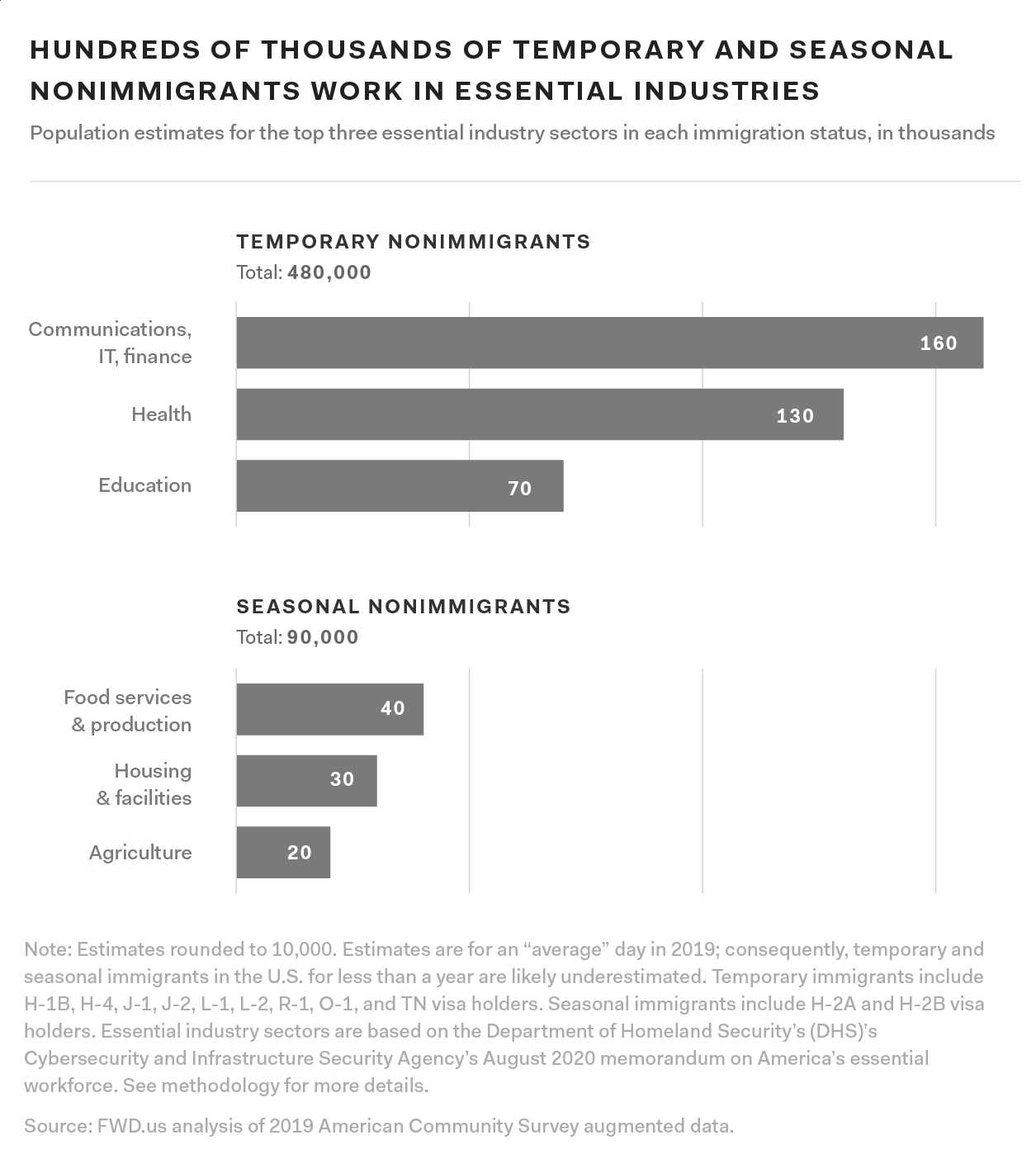

Some 250,000 Dreamers, as defined by the 2019 American Dream and Promise Act, provide essential work in food services and production. About the same number work in housing and facilities industries, including construction and landscaping services, and an additional 110,000 work in health industries. Across all essential sectors, an estimated 1 million Dreamers work in essential industries, making up nearly half of the total Dreamer population.

Finally, an estimated 4.3 million undocumented immigrants, besides Dreamers, work in essential industries, including nearly 1.8 million working in housing and facilities, an additional 1 million providing food services, and more than 400,000 transporting and distributing these materials, among other products.

The future ability of immigrant essential workers to reside in the U.S. is uncertain. Many of these immigrant essential workers, even facing their own uncertain futures, continue to serve on the front lines combating the pandemic. They work despite not knowing whether they will be able to continue living in the United States next year, next month, or even tomorrow.

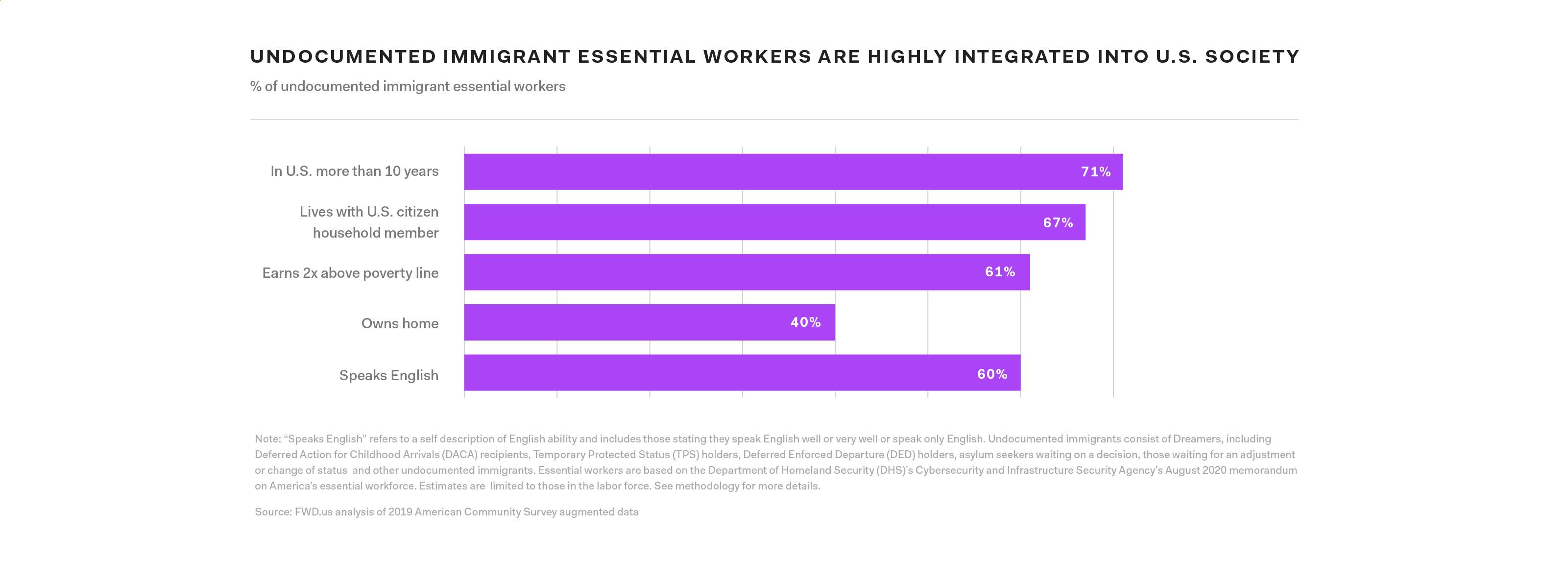

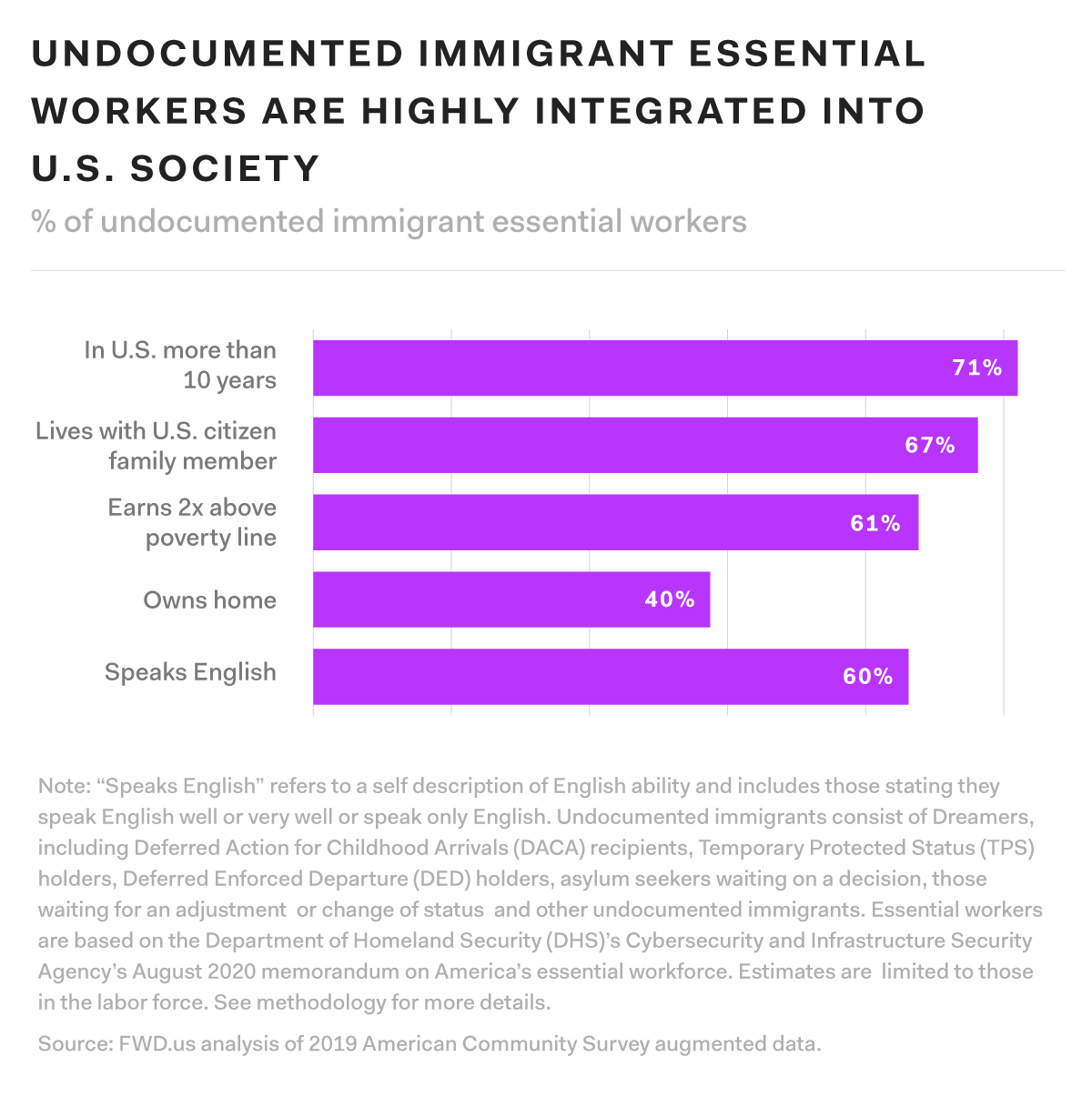

Most undocumented essential workers have lived in the U.S. for more than a decade, live with U.S. citizen household members, and are financially stable

Undocumented immigrant essential workers, including Dreamers, are well established in U.S. communities, with most (71%) living in the U.S. for ten years or longer. They have built their lives here, and their communities have come to rely on them.

“Some 7 million U.S. citizens, including 4 million minor U.S. citizen children, live with undocumented immigrant essential workers.”

At the same time, about half (52%) of undocumented immigrant essential workers are married and have their spouse living with them. More than half (57%) have at least one child living in the household. The majority (67%) live with at least one U.S. citizen household member. In fact, estimates show some 7 million U.S. citizens, including 4 million minor U.S. citizen children, live with undocumented immigrant essential workers.

Most undocumented immigrant essential worker families (61%) live at two times or higher than the poverty level in their communities. Nearly 4 in 10 (40%) undocumented immigrant essential worker families own their own home. Consequently, most undocumented immigrant essential workers are financially stable and they are, on average, at a similar economic standing as lawful permanent resident essential workers.

Meanwhile, most (60%) undocumented immigrant essential workers say they speak English well, very well, or speak only English. Also, the majority (60%) of undocumented immigrant essential workers have completed a high school or higher level of education.

With their unique and essential work skills, their integral role in U.S. communities, and their financial stability, these undocumented immigrant essential workers are vital to the COVID-19 economic recovery. They have been an integral part of the U.S. economy for many years, and will remain so in the years ahead.

Methodology

Footnotes

- Estimates presented in this report are based on data from the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS), an annual, nationally representative survey of 3 million people conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. ACS respondents are not asked about their immigration status; consequently, immigrants in the survey are assigned different statuses based on other information they provide, including their occupation, their family relationships, government services they use, their country of origin, time in the U.S., and other characteristics. The assignment method is similar to that used by other immigration research and policy organizations, and includes population adjustments for potential undercounting in the survey, particularly among undocumented immigrants. A full methodology is available here.

- The number of undocumented immigrant agricultural workers is likely higher, perhaps more than a million. The million figure is based on an estimated half of the more than two million estimated agricultural workers nationwide. The American Community Survey (ACS) data used in this report likely undercounts the number of agricultural workers as they are mostly seasonal and transient workers, sometimes out of ACS’ reach.

- FWD.us analysis of Current Population Survey (CPS) data in essential industries, as made available from Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles and J. Robert Warren. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 8.0 (dataset). Minneapolis: IPUMS, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V8.0.

- Midwest states include Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.

- COVID-19 infection estimates by immigration status are based on state race and ethnicity data from March through October 2020, adjusted for age and sex, from national case data from the CDC. These incidence rates were applied randomly to respondents within the 2018 ACS to ascertain estimates of COVID-19 cases by immigration status.

- Disposable income, or spending power, is total personal income based on ACS data, after estimated federal, state and local tax payments. Total federal tax and payroll estimates are based on tax rates of market income by household type and household size from the Congressional Budget Office’s 2017 “Distribution of Household Income” report. Total state and local taxes are based on share estimates of income from the Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy’s 2018 report “Who Pays? A Distribution Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States.”.

- Essential industry sectors presented in this report reflect categories presented in that memo. A full description of the industries considered essential can be found here. More than three-quarters (79%) of the total U.S. workforce, regardless of immigration status, is employed in essential industries.

- By this definition, about half (49%) of the total U.S. workforce includes essential workers on the front lines.

- Foreign-born does not include those born in U.S. territories or born to U.S. citizen parents abroad.

- The total undocumented immigrant population was estimated to be some 10 million people in 2019.

- Many more H-2A and H-2B visas in essential industries are granted annually than those shown in this report. The estimates in this report are for an “average” day in 2019. Since not all seasonal workers stay in the U.S. the entire year, the report’s estimates for this population are lower compared with the higher number of visas granted annually.

Tell the world; share this article via...

Read related articles:

Get Involved

We need your help to move America forward. Learn what you can do.